A Short Story by Chris Riker

“…you were killed instantly, dying at the age of sixty-three, and were heavily mourned by your family and community,” said my voice as I read from the parchment in my hands. The dread that defined my life on Earth had come to fruition. I was stunned but not surprised.

“…you were killed instantly, dying at the age of sixty-three, and were heavily mourned by your family and community,” said my voice as I read from the parchment in my hands. The dread that defined my life on Earth had come to fruition. I was stunned but not surprised.

“Not bad,” the robed man across the desk from me said in heavily accented English. He called himself Mohsine. He lifted the velum scroll from my hand, reached over, and slid it into a pigeonholed case that took up one wall. The furnishings in the room suggested a railway depot circa 1870’s, albeit one formed of thoughts and will rather than solid matter.

A Tonkinese kitten napping in one of the pigeonholes awoke with a start and shot out of its lair like a hairy cannonball, in the process scattering life scrolls onto the floor. Mohsine picked them up. “The universe is absurd. In the end, the scrolls record how we react to things beyond our control. Our anima sisters and brothers get written up in all sorts of ways, some of them most distressing. Don’t worry, you did well.”

“Thanks, I guess. It’s my first time being dead.”

“Hardly,” said Mohsine.

“What about my family?” The scroll said they mourned me, though for the life of me I didn’t know why. I had never done anything to make them proud. I had such big dreams, but what had they gotten me? I left Lara with a pathetic insurance policy and a mortgage I should have paid off years ago. No property, no pension, nothing for the grandkids. I was a failure and now it was too late.

“For them, time is passing. I can tell you they are sad but coping.” He smiled and scratched an earlobe.

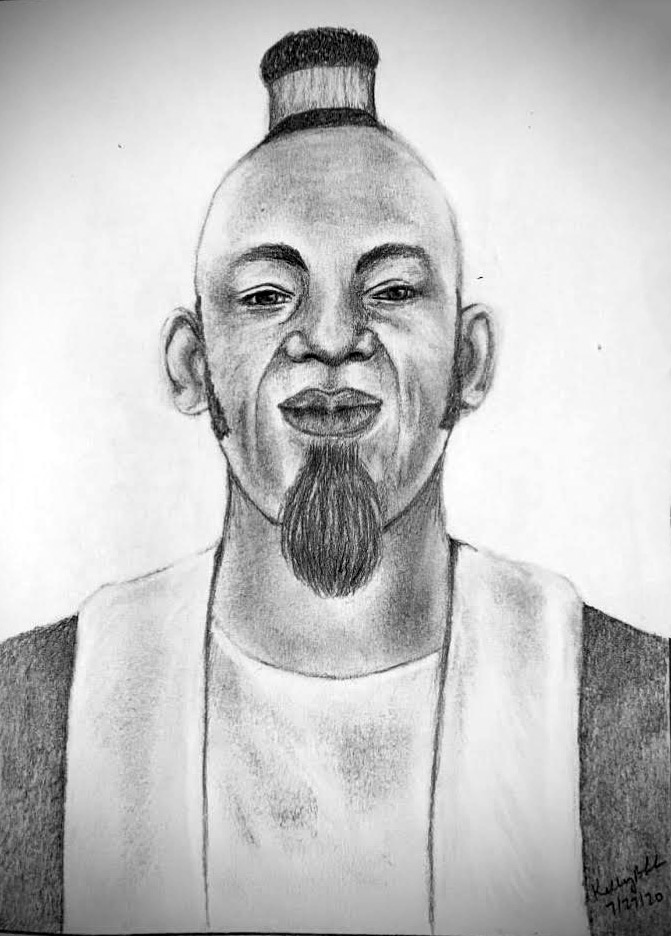

I noticed how strikingly different he and I appeared. My terrestrial bloodline was a mix of English, Irish, Dutch, and Swedish. I was six-one, with dark hair (less gray than I remembered in fact), pale skin, and blue eyes. Mohsine was somewhat shorter and had powerful limbs, brown eyes, full lips, a broad nose, and a tawny complexion. I found my own clothing unremarkable (jeans and a sport shirt), but Mohsine looked imposing in his loose-fitting green robes. He had shaved his head except for a modest circle of frizz on the top which he grew to about a hand’s width and wore bound up in a colorful ribbon. Sideburns framed his face while a beard hung from the tip of his chin.

My next words came out before I could stop myself. “Are you God?”

From deep inside, Mohsine released a thunderous laugh that shook the room. “No, we are not.” He grinned warmly. I wanted to say something, but it was difficult to maintain my mental footing. “I’m trying to explain, I am you in a previous form. Distinct yet fundamentally bonded. You and I are but two of the many turns our soul has taken so far on Earth. This depot exists… between lives.” This was going to take some getting used to. “There are many of us,” he said, indicating the rows of scrolls in the bin. I concentrated but could not make a firm count of how many scrolls were there or how many slots were yet to be filled. “A word of advice. Later, when you meet the rest of us, if they offer their views on God or gods… or power… or money… or sports… or any such trivialities… smile and nod your head.”

“Fine, but then who is in charge of things?”

“No one, not in the way you mean,” Mohsine said, shrugging, then added, “although Falafel thinks she runs the whole dimension.” The kitten now sat on the desk, giving herself a tongue bath.

My brain hurt. From my point of view, the wreck had happened minutes ago. Working late at a job I hated, driving home in bad weather, bright lights; I honestly did not know whether I had crossed the center line, or the other driver had. Now, here I sat in a depot outside of time. It was a bit much.

Mohsine saw my discomfort and offered me a Coke in a cup crudely fashioned from a gourd. It was not the only anachronism battling the room’s decor. A kitschy snow globe of Boston sat on the desk, flurrying perpetually though no one had shaken it. An antique pendulum swung below a digital wall clock. “Ice?” Mohsine asked. I nodded and several cubes appeared above my cup and plopped into the fizzy cola.

“Cool!” I said. He shot me a paternal look to say my pun was childish.

“The creature comforts of the twenty-first century. I never saw ice – not a lot of it in sixteenth century Morocco.” He drank steaming mint tea from a small glass imprinted with Van Gogh’s Starry Night.

Mohsine was not how I pictured myself in a past life, not that I’d expended a great deal of thought on that subject. I spent more time regretting the dreams I let wither. If I had thought about it at all, I’m sure it was a matter of celebrity worship, fancying that I had once been Mozart or Julius Caesar or Lord Byron. Turns out I’d been an old Moroccan named Mo. Makes you go, ‘Huh.’ I said as much to Mohsine. “I was more of an Egypt buff. Pyramids, mummies! I’m afraid I never read up on ancient Morocco.”

“Ancient? I took my earthly turn barely five centuries before yours, Geoff. Wait til you meet Oona’loo’lolla. Then talk to me about ancient things.”

“When will I meet… her?” I asked, though I was in no hurry. It was strange enough to be speaking with this iteration of myself.

“When you’re ready.” Mohsine stood up and stretched. “You’ll reunite with all of us, all of yourselves – clumsy grammar – soon enough. It is easy to get lost in such a hall of mirrors. It’s best for the newly arrived–"

“You mean the newly dead.”

“As you wish. It’s best to take things slowly. For that reason, I have come to help you find your way before you bestow your Ātman upon the child.”

“My Ātman? What child?”

“It’s what we do here, Geoff.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“A wonderful suggestion. Follow me!” He grabbed my hand, pulled me out of my chair, and took us at a full run out of the depot. We sped from where we were to where he wanted us to go. The sparse, non-descript scenery slid by. Colors changed and musical chords rose and fell. “Do you like dolphins?” Mohsine asked.

“Sure.”

“Cool!” he said, flashing a mischievous smirk.

With that, we were wet. In fact, we were suddenly stretched out prone, floating deep in an ambient, almost amniotic, sea. A pair of sleek dolphins appeared and began to circle us, looking us up and down as if to take our measure. One was slightly pink in color; the other, which paired off with me, was bluish. So many times in my life I had told my wife I wanted to go swimming with dolphins, but somehow, I never made it happen.

Something occurred to me. “I’m breathing underwater!” I cried, less with alarm than an urge to narrate my own surprise.

“It’s better than not breathing. Now we must lock our knees, keep our backs straight, and let Reyad and Zinba do the rest.”

A bony rostrum gently but firmly planted itself against the soles of my bare (when had that happened?) feet and pushed. Reyad’s powerful tail whipped the water behind us, and we gained speed. I struggled to keep myself as aquadynamic as possible.

With a sense I did not recognize, I became aware of our travel. We were moving in the water but also in other ways that had nothing to do with the three dimensions I took for granted. Mohsine tried to explain, though I confess his words didn’t make a lot of sense: “While we are here, between one life and another, our sense of place and time is shattered. The sparkly shards fly about in a lovely chaos. Time flows as it will rather than how you are used to.” Good to know.

Turning my attention to the surface of the water, I saw hulls traveling in all directions. I perceived more about these vessels than I should have been able to take in from our undersea vantage point, and yet I was comfortable with this extra sight. It was as though I’d had it all my life and was only now getting the chance to use it.

I focused in on a simple raft, crewed by men and women who were filled with the spirit of exploration. They had learned to lash together bundled reeds and ride the ocean currents to a new land. A moment… or a few thousand years later, a fleet of wooden ships with dragon-headed prows split the waves above. These longboats were filled with brutal seekers who lived to spill blood and seize gold and land. Vessels of all configurations came and went. Men piloted them, carrying goods and settlers. Sailing ships also carried human cargo in their stinking bellies while the men on deck went about their duties indifferent to the misery below their feet.

Words came with great effort. I said, “I want to talk to them. I want to tell them something,” I pleaded.

“Do not concern yourself. We are in-between. Those men you see will not be affected by us.” Mohsine’s voice took on a tone of sadness. “It gets worse.”

Reyad and Zinba were pushing us upwards towards the surface… then we burst through it into the air. Up and up we went, perhaps a thousand miles. It seems redundant to say that this existence in which I found myself had a dream quality to it, but here we were. Dolphins could fly. I could fly. Why not?

Below, my eyes gathered vast sweeps of land in startling detail. I could see villages surrounded by untamed land. These settlements hardened, the buildings morphing from crude wooden lodges to fine buildings of stone and then steel and glass. The growth accelerated, metastasized. The forests and wild places thinned and retreated until the manmade dwellings outsized the natural domains. Then for no apparent reason the advance came to a halt. I recognized the designs, the roads, the filth of my own time. From our place far above, I saw what I’d never been able to see in my life. The Earth was covered in a solid mass of human flesh and was drowning in the poisons we produced, both land and sea.

“This is the present. My time.”

“Yes.”

“And the future?” I asked.

“Is what we are here to bring about,” Mohsine answered.

“Bring it about. I want to stop it. End the destruction before it’s too late.” Perhaps even now I might make a difference, I thought, but it was not going to happen.

“We can do what we can do. Focus on your Ātman, Geoff. Perhaps the Ātman you choose to give our child will be compassion.”

It finally dawned on me what he was talking about -- that our child, Mohsine and my child, was our next life on Earth.

“You’re saying I can give our successor the benefit of my knowledge.”

“Wisdom... and knowledge are earned between the womb and the grave. They are of great value but do not easily translate from one life to another. What if, before you were born, I had wished you all my knowledge of spice trading, what would you have done? Been an American nutmeg trader at the age of five? Such knowledge would have limited you in ways you cannot imagine. No, each Ātman is a facet in the child’s true self. While lives begin and end, the Ātman grows over many lives.”

I knew this was important, but my mind groped to find context. “I am trying, but I’m not sure I understand. What exactly is an Ātman?” I asked.

“Think of an Ātman as a general sensibility that colors our choices. Our past selves contribute new parts. One part may take dominance at times or lurk in the background as a series of preferences. Each may duel with others, but each is there to help us meet whatever situations life presents us.”

“What are my choices? Can I tell our child to be fat, dumb, and happy?”

“More than one of our kind have tried that. I hope your choice is more… evolved. Would you like to know what others chose for you?”

“Yes!”

Mohsine issued a series of clicks, whistles, and chirps to our dolphins who responded by taking us down to the waters of the Mediterranean. They set a new course and sped us through the sea. In a heartbeat (yes, I still appeared to have one) we were stepping out of the waves and walking up the rocky shore to an impossibly tall pink granite structure. It was millennia more primitive in design than the skyscrapers I had recently viewed, but unequalled in grandeur in any time or place. Pharos. The Lighthouse at Alexandria.

Mohsine issued a series of clicks, whistles, and chirps to our dolphins who responded by taking us down to the waters of the Mediterranean. They set a new course and sped us through the sea. In a heartbeat (yes, I still appeared to have one) we were stepping out of the waves and walking up the rocky shore to an impossibly tall pink granite structure. It was millennia more primitive in design than the skyscrapers I had recently viewed, but unequalled in grandeur in any time or place. Pharos. The Lighthouse at Alexandria.

Every edge was unweathered, freshly hewn. We ascended the cool limestone steps on the water side, one face over from the tower’s great pedestrian causeway, and passed through a colonnade topped by statues of Ptolemy II and his queen. Mohsine pointed to a plaque on one wall. “No!” I cried in happy disbelief. It was the plastered false front stamped onto the great wonder by its architect. Though I could not read it, I knew it gave all glory to the pharaoh. Therein lay the joke. In a century or two, the plaster would flake away, revealing the permanently engraved mark of the architect.

Standing in the courtyard, I strained my neck to take in the tower’s dizzying four-hundred-foot height. “I’ve always wanted to see this!”

“I know,” Mohsine said.

“Wait, you dreamed of seeing the lighthouse too?”

“The wonder of it has inspired dreamers for centuries even though great tremors claimed the light.” I strained to remember my history. Mohsine would have been born about half-a-century after workers recycled the last tumbledown stones of the lighthouse into a fortress.

“So, I got that desire from you?”

“Perhaps.”

“Is that an Ātman?”

“No, just some of the flotsam that drift from life to life. A weakness for puns, a love of artichokes. Quirky sorts of things. The bits never add up to much but they make us interesting.”

“Can we go up?”

As Mohsine said “Yes” we rose, passing windows and the square landing that presented visitors with statues of Triton the sea god at each corner. Up we went above the central eight-sided segment to the apex chamber and the lamp itself. This cupola was topped off by an enormous statue of Poseidon, visible to sailors in the Great Harbor… and from the royal barge with its aerial escort of sea birds. From the lamp room the view of Alexandria stretched out below us. My breath caught in my throat as I recognized the famed library, storehouse of all the knowledge gathered from across the ancient world. I indulged myself an immodest comparison: I had become the storehouse of an Ātman that would, hopefully, benefit my future self. If only I knew what that Ātman was to be.

Behind us, mounted in a pivoting cradle stood a parabolic mirror made of brightly polished bronze. “Does it light up?” I asked eagerly.

“At night.” And it was night. A furnace flared to life in front of the mirror. Mohsine and I laughed at the cheap theatrics. “Now then, you were wondering about the Ātmans of the past? Let’s spell them out.”

A fog bank was rolling in off the water like a moving mountain range. The mirror caught and focused the light, but instead of projecting a single beam, it flung thousands of colorful rays onto the misty wall. The effect reminded me of a laser light show. Once again, this realm of existence glibly borrowed from the times of our lives and mixed elements with mad abandon.

“Behold the Ātmans that have help shaped yours and my lives,” Mohsine said. And he read from the fog bank: “‘All unfolds with divine timing, be patient.’ Laura. She was a precious soul, beyond earthly measure. Oh, what am I saying was? She still is!” From somewhere in the fog, I heard Reyad and Zinba chattering to each other in a sort of animated commentary.

“‘Gratitude.’ Our sister Annabelle added this single word to the mix a century and a half ago. Daughter, wife, and mother of six, she dreamed of breaking away from her hard life in West Virginia’s coal mining country and discovering her full potential. She never marveled at the lights of Paris, and yet at the end of her sixty-eight years she closed her eyes on the world with a contented heart.”

I envied Annabelle’s turn at our existence. I hated my aimlessness. How wonderful would it be if I could be grateful for my life instead of regretting my mediocrity. She had cleansed herself of resentments like those that weighed on my spirit. I strongly considered following her lead and committing to offering the child an Ātman of gratitude.

Mohsine was looking at me and seemed to know I was looking inward. He patted the granite balcony. “We were here, you know. One of our number was among the hundreds who labored in the blistering sun to build this place. He gifted us an Ātman: ‘Do not falter. Work on.’

“Some of our anima clan were more, shall we say, pragmatic.” ‘Take. Do. Eat well,’ shone the light in garish reds and golds one might expect in the draperies adorning a brothel. “That was Vyacheslav,” Mohsine explained. “He was a drinker and a lover. A bit fat. When you meet him, don’t ask about his cousin.” He squeezed his lips between his forefinger and thumb, basically saying ‘Shh.’ I filed away the tip.

More colors flashed out into the night, greens, umbers, and violets. “Other entries along those lines include: ‘Succeed!’ … ‘Dominate!’ … and ‘Never make mercy your business partner.’ “There are many more, but I expect you’d like to see one of us saying this.” The lamp turned silvery blue and spelled out, ‘Love is all - let it out and let it in.’ “It’s a shared sentiment from Elna and also from Duangkamol. Two dear ones. Elna died without regret while cradling her fifteenth great grandchild. Duangkamol never once lied about her feelings. She lived to love… and fortunate men loved her.”

I could sense each of those sentiments in my own memories and feelings. I wondered, then, with so many helping me why I felt so conflicted in my life. Why did the thought of the life I’d now concluded fill me with profound disappointment?

The fierce lamplight fused to a single beam of amber-tinged white cutting through the fog and darkness. It seemed almost banal by comparison. The show was over. Mohsine and I looked at one another.

“When do I bestow my Ātman?” I asked.

“When we get there, of course.”

I sensed no deception from Mohsine. There was no way he could lie to me. I had to be patient and accept the way he presented the information to me.

It was time to go. This time, we walked down the winding steps inside the tower. It was exhausting, but fascinating at the same time.

“You are troubled in your choice?”

“Yes. I want to do the right thing for this child.”

“That may be harder than you imagine.”

We passed visitors to the lighthouse on our way to the shore. No one turned their head as we stepped into the water and kept going. Reyad and Zinba met us below the surface, eager to be off.

“Where are they taking us?” I asked.

“To my home and my time.”

The sea around us lightened. It took only moments, but we were soon far away, in a different ocean.

“In case you wished to know, empathy was dominant among all my spiritual gifts while I walked the Earth. A good choice. I pass it along myself occasionally. And yet… no Ātman, not even empathy, is without its dangers.”

Our dolphin guides brought us to a crowded harbor then happily darted away. We stepped from the water onto narrow streets made of flat stones and crushed shells. We found our footwear returned, sneakers for me and balgha for Mo, and our clothes dry, both my jeans and Mohsine’s gray and olive-colored djellaba. (The words of his life were now familiar.)

“Agadir,” announced Mohsine. “Home.” We stood in a gleaming white port city near the foot of the Atlas Mountains where the Souss River flows into the Atlantic. “Five-hundred years ago, this was the beating heart of Morocco’s culture and source of its great wealth.”

Pungent smells stung our nostrils from open air market stalls and livestock pens tucked into every odd space. People dressed in glorious fashions passed us on the street, bustling into and out of small shops and homes. The women wore jewelry of silver, pounded copper, and gold and on their faces intricate geometrical tattoos. The architecture reflected Morocco’s long history as both conqueror and conquered. I noticed the people’s Berber tastes, residual Roman influences especially around the columns, and an echo of Byzantine style.

Mohsine led me to his own shop and explained what we were about to see. As he called up memories from his own life, faint shadows darted in and out of our field of vision, overlaid on this ‘present.’ Like Scrooge traveling with the Ghost of Christmas Past, I was a shadow here.

We sat down at a café overlooking the boats anchored in the brilliant blue cove. A hungry dog circled our table, which the owner set with a tray of fish and mssemen bread drizzled in honey. I didn’t realize how good eating could still feel; the fried bread and honey filled me with a sweet delight. Knowing I was left-handed, Mohsine reminded me to eat only with my right, in deference to Muslim custom. He then poured me a cup of mint tea and began his story.

“In the final days of the Wattasid kings, I was born into a family of wealth and standing. My father was a merchant, trading in finely worked leathers, brightly hued rugs, brass utilities of all sorts, argan oil for cooking, and when he could find nothing better to sell, hashish. He traveled often, leaving me to protect our home and look after my mother and younger brothers. I filled my heart and head with more concerns than a boy my age should until I was an old man of thirteen. Childhood passed me by on the street without a nod of recognition.

“Even as a boy, I looked out on the world and felt its pain. I could not bear to see people with no morsel of food or protection from the ocean’s cold night breath. I took bread and blankets from home and gave them freely. One day, my father spotted me doing this and grabbed my slender reed of an arm so tightly I was sure he would break it. He scolded me, saying, ‘Foolish boy. You give away all that I have earned and for what? These people will only follow you and demand more. One day your wealth will be gone, but their want will never fade. They will grow angry when you can give no more.’ His words stung, but I reluctantly obeyed his commands. I wanted to please that man more than I wanted my life.

“Once I had attained fifteen summers, I traveled with him. We visited new and strange lands, far from home. I learned quickly from my father how to spot quality but had difficulty with his way of negotiating prices. I felt that those selling an item had a right to earn what price they wished for their goods. I watched silently as my father spoke faster and louder than the merchants he dealt with. He convinced them that their goods were of poor quality and barely worth his labor to haul them back to Agadir. He told them only by chance might a drunken sailor relieve his shop of such dreck.

“I never spoke of my feelings, but I confess to you now that my father disappointed me. His cynical views threatened to turn my heart bitter. My father and I argued like two lions. Our tempers grew hot; he accused me of trying to live in paradise blind to the real world and I accused him of stealing from merchants who had families to feed. I demanded my freedom, and he allowed me to leave home with a few possessions and a light purse.

“I fashioned my life, action by action, day by day. I knew how to trade, though I offered better prices than my father had. This made me welcome in marketplaces up and down the coast. People called me an honest man, and I cherished this praise. My reputation for charity and kindness spread and brought me more wealth than I ever expected.

“One merchant with whom I traded frequently had a daughter with eyes dark as dates and hips that filled my nights with– She was all that I ever knew of love and I married her. She bore me three strong sons and a caring daughter. In time, my sons came into my growing business.

“After years of traveling from one bazaar to the next, I acquired a shop of my own. I expanded again and again, trading in many of the goods my father had taught me to sell, plus silks brought in by the men who traveled the seas. Our reputation turned to gold. Soon, the work was more than my sons and I could finish by nightfall. My sons, meanwhile, felt the same wanderlust I had known at their age.

“Not for the first time, I regretted having been severed from my siblings and cousins, whom I now might have offered a place in my enterprises. Instead, I hired a handful of young men. I found them struggling to survive in dark alleyways and offered them hard work plus a wage to meet their needs. I trained them and eventually entrusted them to tend my shop while I and my sons went abroad.

“One day, I returned from my travels, having left my sons to conclude some business in Rabat. I was in my sixties by this time and tired. I dreamed of nothing more than coming home. Ever mindful of my business, however, I decided to stop and check on things before returning to my wife and bed.

“I found one of my hired men stealing from my shop, loading a cart out back. I saw the guilt in his face and yelled at him. I called him ungrateful and scolded him in my father’s voice. And while my mind was hurling bitter words, the man picked up a jeweled cane taken from my own tables and bludgeoned me over the head. I fell to the hard street and bled to death mere steps from the shop that had been so much of my life. The man took his stolen goods and struck out for distant lands, leaving behind his filthy name.

“My son found me a day later. My family and people in the community mourned my death with copious tears but also with laughter and food and drink, as I had always wished.”

“I’m sorry.” I didn’t know what else to say.

“I am not. I understand now that I was not wrong to share with others what little I could. Even so, there are always those who will repay kindness with selfishness and violence. They harm themselves. When they brutishly clutch a handful of riches, they drop the opportunity to grow.

“I must accept that I can show such people the way, but I cannot make them take the steps. It is the nature of free will. Instead of jumping in to try and solve another’s problems, I must offer simple guidance. I will not call it a regret, but I will say that I wish I had put my family ahead of my business pursuits. Beyond that, I am happy and at peace.”

Mohsine had exposed his inner self to show me that any Ātman I might choose could create risks for the child. We walked silently for a time. I did not pay attention to the shifting surroundings, but I knew we were no longer in Agadir.

We came to the place of renewal. It was a launching spot for a new beginning on Earth. We joined a circle of quintessence, all my past selves, including those we had acknowledged in our conversation. They displayed soft edges and subtly different hues, no two alike. I could not discern their features or even count their number. Mohsine assured me they would resolve into sharp relief soon enough.

For now, what was important was the child, there in the middle of our circle. It was literally indescribable, real but with no race or gender, lacking all detail yet perfect in its potential. I had no way of knowing where this child’s life would begin on Earth or how much time had passed since my own story’s conclusion. None of that mattered. What mattered was the child.

“Take one last moment to consider your gift to this new life of ours. I have made my choice.” Mohsine stepped up to the child and spoke from the heart: "Be true to yourself." From nowhere, Falafel, the kitten I had met at the depot, came running up, ears back, eyes two balls of hot murder. She leapt onto him and used her claws as pitons to scale Mount Mohsine until he plucked her from the weave of his robes and cradled her harmlessly against his shoulder. “She approves of my choice,” he said, stroking the now purring beast.

I thought about what Mohsine had told me. I had not done anything with my life as interesting as he had done. I had never trekked alone to distant lands where I did not speak the language. I had held jobs but never started my own business. I had certainly fought with my father but never stood up to him or struck off on my own. I had been many things, but never… Something always held me back, something lurking below my consciousness. Some inner flaw.

Yet, what did it matter now? I was done with worldly concerns. I could look at them for what they were: momentary distractions. And if my failings meant nothing now, I wondered whether those great mistakes and doubts had ever meant anything at all?

I looked to Mohsine and he seemed to read me perfectly. He raised his head slightly and his eyes creased with approval. The effect was wonderful. It was as if I were a hot air balloon casting off from my moorings, suddenly free from the tethers that held me to the Earth. I could rise.

In that moment, I knew what to say to the child.

I stepped forward, closed my eyes, and spoke: “Be gentle with yourself. You are a good soul.”