She walked away one hazy Georgia morning

Left her dreams in pieces – no one cared

The kids all grown, his heart a stone

No one warned her life’s not fair

Some days will take you far away

To places you weren’t meant to go

Making wishes that’re better left alone

Walking barefoot through a silent world of snow

Some days… you find… there just ain’t no way home

She knew all life’s little secrets when she was three and twenty

Tomorrow was a million miles away

Who knew she’d meet such sadness in sex and love and money?

Thirty-six found her weary and turning gray

That day you look up and see only blue

Is the day you learn to lean on only you

Making wishes is for fishes and for little girls in curls

Making love and making life is for us all

Some days… you find… yourself wishing you were home

Some days will take you far away

To places you weren’t meant to go

Making wishes that’re better left alone

Walking barefoot through a silent world of snow

Some days… you find… there just ain’t no way home

She walked away one hazy Georgia morning

###

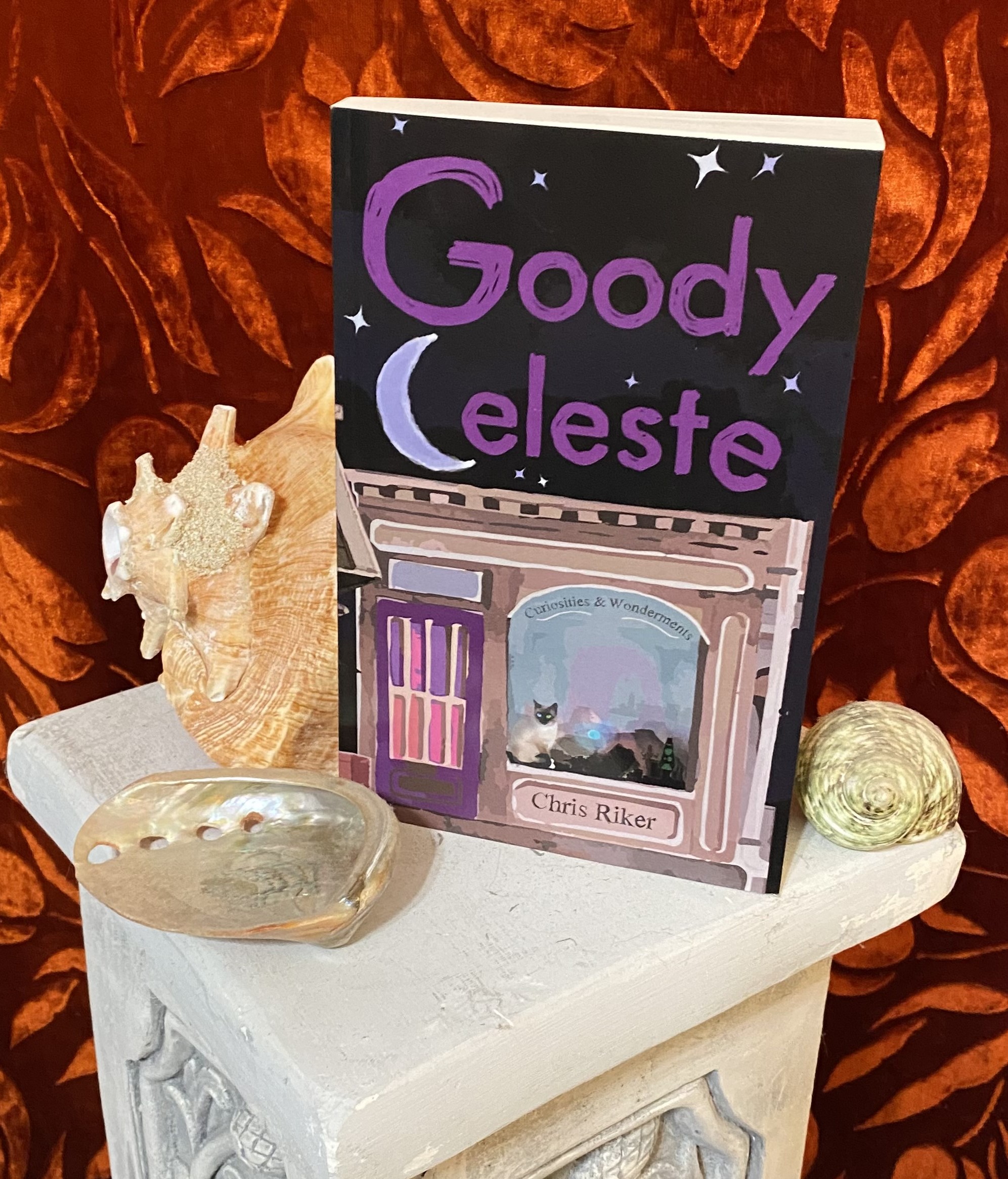

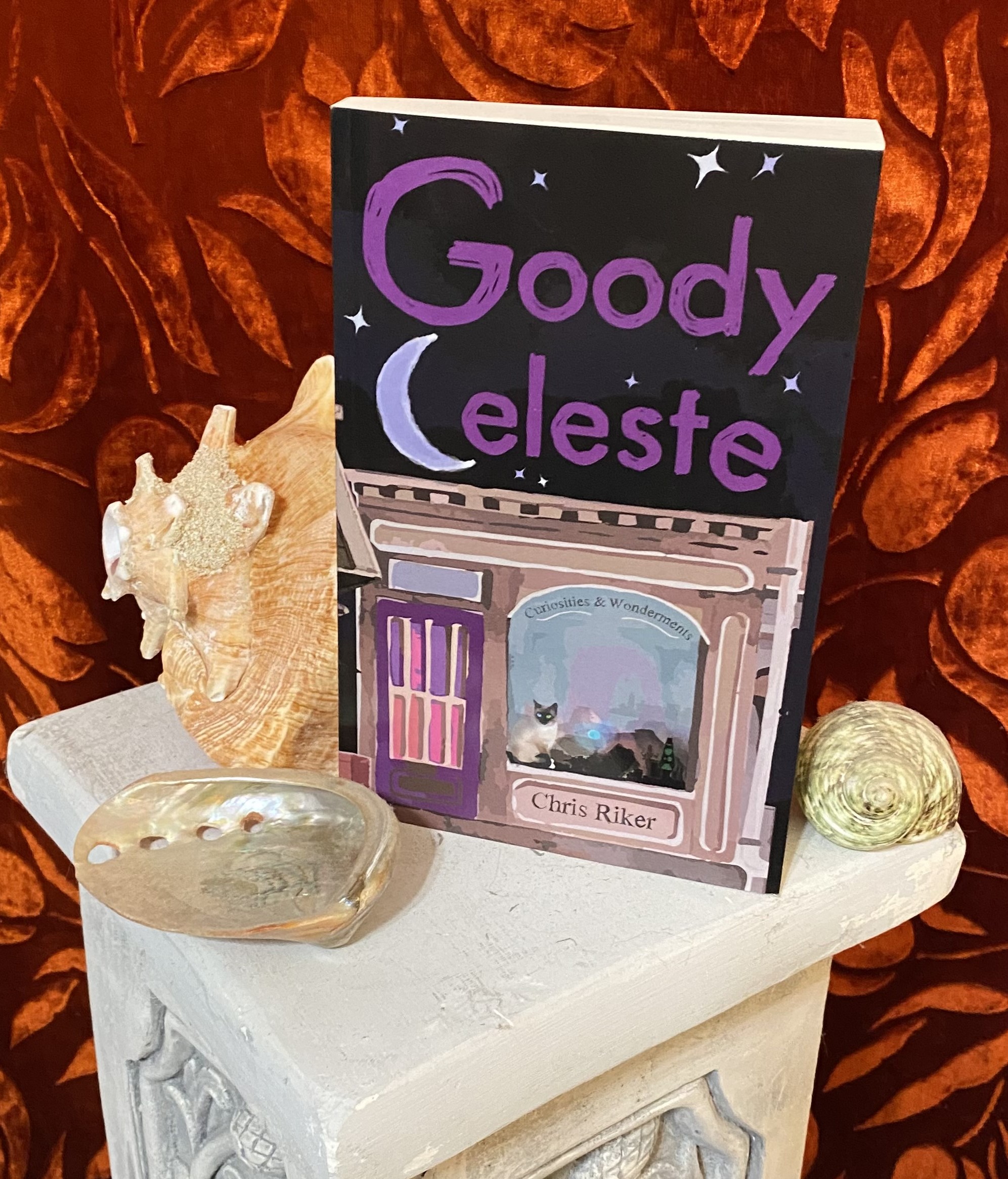

If you like stories with feels, I think you'll enjoy:

https://www.amazon.com/Goody-Celeste-Chris-Riker/dp/1665307072/

Here's a preview: https://chrisrikerauthor.com/news/short-stories/a-story-of-summer-and-youth-and-why-girls-are-scarier-than-the-house-of-horrors

- Details

How to say I love you

sans roses, violets red and blue?

Dare I declare you are

my best old pair of shoes?

For a poem, I called to Shakespeare’s ghost

Turns out he’s sleeping late

I hoped Byron or Keats might write a gem

but I can’t afford their rate

So, I scribbled what I could

with my stiff and feeble hands

of how I love you so

with my heart and with my glands

*sigh*

You see, no talent do I own

to name my truest love

I say you’re like snug shoes

They are, like you, all I think of

Nothing matters more than shoes

when worlds turn bitter cold

Pricey footwear thrills me not

Good shoes fit best when old

My shoes are there for me

at times I need them most

I’ll never trade old shoes away

for new ones – that’d be gross!

I need, I want, I love my shoes,

the perfect well-worn pair

I’ll love Shoe Ping the more

we tramp on through our years

- Details

A brilliant future called to my boy thanks to the long years I’d devoted to my project. Between commuting into Manhattan for my hump of a job and spending my nights in the tiny lab I’d set up in the turret of our aging Victorian in Hempstead, I felt that twinge all fathers feel at short-changing Yuchen. No long talks. No scary movies shared with the lights off. No playing catch in the backyard – my father had never done that; did any fathers do that? No matter. Yuchen would understand. One day the project would pay off. I was so close. I would repay him a million-fold with wealth and prominence few sons ever enjoyed. Still, I felt that twinge.

So, imagine my joy when I found Yuchen working on the Qilin, calibrating it just the way I’d taught him. That is, I’d talked about it over the dinner table. He must have absorbed the knowledge. Kids are like that, so open; they take things in through osmosis. In any case, his tiny hands moved over the screen, adjusting one submaster and then the next in turn. The pattern form monitor came ever closer to resolving into a solid golden thread. Closer than I’d ever gotten, certainly. My pride swelled.

*

“He’s eleven,” Bethany said, clearing her and the children’s dinner dishes as I sat down to eat. She’d used a lot of paprika in the chicken. Unless this was pork. “Eleven-year-old boys shouldn’t have their faces in Mesh pads, trying to punch holes in the fabric of the universe.” She had a point, of course. Still, the Qilin would change a lot of things. Who knew what eleven-year-olds would be doing in a few short years – if my project succeeded. One thing was for certain; I’d be able to take us out to dinner for something better than Bethany’s spice-crazed chicken.

"He’s a prodigy, Behny.” She made that face she made for some reason whenever I said her name aloud.

“He wasn’t a prodigy in school last week.” Her voice cracked. She wasn’t watching her tone, since the kids were upstairs. I’d locked the turret room. Not that I didn’t want Yuchen’s remarkable help, but I didn’t want him in there without me, and the idea of Bethany or Elsbeth screwing up my work drove me nuts. If they got in there, I’d absolutely kill them! I needed just a little more time without interference. The Qilin was close to being operational. Once the signal found its target, the cranial anchoring unit I’d planned would practically build itself. I flipped the app in my Mesh and checked the preliminary design for the tenth time. The Mesh was such a limited device. Let the Qilin peer a few decades ahead and such crude gadgets will become as obsolete as an abacus. A few simple steps to go and I’d be more famous than Einstein, and richer than –

“Feng?”

“What? Uh, what was last week?”

“Good lord, Feng, our son got sent home for screaming at his teacher. He called her – well, it wasn’t a nice name that he called her. Sixth grade and he talks like a sailor. Elsbeth says he just started talking that way, not three weeks ago. She says he’s getting worse. She doesn’t want to play with him anymore. They were so close, Feng. A boy needs a sibling to play with… and a father. Are you listening to me?”

I had a few more calculations to do on my Mesh. If I could get this rider program to mate with the main polyalgorithm, it would save a fortune in time by –

“ARE YOU LISTENING?” Bethany stood over me, my Mesh in one of her hands and a greasy plate in the other.

“I’ll talk to Yuchen,” I said. She reluctantly handed back my Mesh.

*

We spoke, though it was difficult to say whether the boy did more than nod politely, as if the conversation were something he’d heard before.

“You must respect your mother, sister, and teachers, no matter how slow or stupid they seem to you and me.”

“They don’t matter,” my eleven-year-old Yuchen said in a half-voice. I grasped his shoulders and turned him to face me with the intent of giving him a stern lecture. Instead, he spoke up. “People can be replaced as needed when one possesses true clarity.”

I did not know how to respond to that. It was not something I remembered saying in his presence, although it was a thought that had occurred to me on occasion. Did osmosis work that way? Certainly, he might follow the same path I had tread and learn the same lessons – but at eleven?

Yuchen returned to his work on the Qilin. The controls were divided among a dozen matrix centers, each with its own Mesh pad, some with two. The matrix layout was cumbersome at this stage, made up of off-the-shelf components. One day, I would use my own designs, fabricating each chip as if it were a porcelain vase from the workshop of the master.

“Do you know the story of the Qilin?” I’d never found the time to tell him stories. His mother read to him from American children’s books that rhymed to numb small minds.

Yuchen stopped what he was doing for a moment. He looked me in the eye and gave me an impish grin. “The Qilin is a kind of chi-mera –” I corrected his little-boy pronunciation “– with the body of a deer and the face of a dragon topped by a single horn. Qilins are welcome harbingers of prosperity.”

He hadn’t mentioned that so gentle are the Qilins they stride the clouds to avoid trampling the grass, or that they only use their remarkable powers on behalf of wise rulers. I prompted, “And do you know why we value its horn?”

He answered haltingly as if by rote. “When one burns the Qilin’s horn like a torch, one can gaze into an illuminated bowl of water to see the future revealed. That’s why you named your machine Qilin.”

“That’s right.”

I meant to compliment my boy for reading up on Chinese mythology. He did not give me the chance to praise him.

Assuming a clear, confident voice, my son told me, “You are a fool, Father.”

His mother was standing open-mouthed in the doorway to the turret room, Elsbeth pressed tightly to her side. It was she who spoke. “What’s wrong with you, Yuchen? You’re scaring us.”

Instead of answering, Yuchen closed the door and locked it, then he returned to his tinkering and calibrating. “You have this tool in your hands, and yet, you don’t know its great potential. I am here to fix that.”

*

For days, we worked side-by-side, making such amazing progress I risked calling in sick to work. If we were as close as I knew we were, I could soon buy and sell my employer. At times, Yuchen seemed moody, immature, saying he wanted to go to his room and play. Mostly, though, he was highly focused and a far better partner in my labors than anyone I’d worked with before. I did not understand how he had come to this level of skill, but I believe it unwise to question good fortune when it presents itself.

I saw little of Elsbeth, though I could hear her sobbing from inside her bedroom. Bethany brought our meals to the turret room, knocking on the door and leaving as soon as I reached out for the tray. One evening, when Yuchen referred to her as “old woman” to her face, she hissed back at him: “Demon!” Afterwards, Bethany had few words for me and instead nursed a chilly contempt.

We slept little. I confess, we bathed less. Hygiene could wait. We were father and son, working together to summon the future. Awe-struck historians would write hefty volumes about Feng and Yuchen Luan.

I spent the last of our savings to purchase some equipment that measured, refined, and integrated the golden thread on the big monitor. At last, the thread hummed on the verge of becoming one crisp line.

Those nights, I rested for a few hours on a sour-smelling couch in the turret room. It had been too long since I dreamt, and so my mind began to incorporate real-world noises into my night visions. I heard the crashing of metal and pictured great cities falling before my eyes. Mighty towers tumbled to ruin, and I stood alone in the wreckage surrounded by broken monuments and broken bodies.

“Will you do the honors?”

Yuchen was standing next to the only other seat in the room, an old recliner with patched holes in its upholstery. Upon this, he’d attached a brace that tilted out with a horseshoe-shaped piece to accommodate a subject’s head. The rest of our equipment lay scattered across the floor in heaps. Many of my paychecks were reduced to trash. All of the equipment that had obsessed my mind and spirit for so long was now mere junk. In its place, Yuchen had put together a single control matrix and display. I’d seen him working on something in recent days, but I’d never seen it in such an impressive state of operation. The device produced a delicate yet intricate tone, and the golden thread on the monitor had braided itself into a helictical pattern of immense beauty.

The Qilin had come.

“Would you like to see, Father? It’s only fair, since you originated this project.”

I didn’t know what to say. How long had I slept? Surely no more than a few hours. In that time, he’d taken the final steps in perfecting the Qilin, my machine to see into the future.

My heart cried out for me to say something worthy of a thick book, something schoolchildren would learn to recite. All that came out was, “Yes, I’d like that. Thank you.”

I sat in the old recliner. Yuchen adjusted the metal horseshoe brace so that it pressed lightly to my temples. There was a slight warmth and I began to feel a bit light-headed. As my thoughts thickened to the consistency of day-old congee, I noticed more details about the array of equipment Yuchen had finished. A second headset, like the one I wore, lay next to the newly finished console. I also saw a miniature tower, about two three in height, standing by the window. It’s lacework structure glowed with a blue hue that was not quite there. “What…?”

“That? It is the logical completion of your work, Father. You built a transmitter to see into the future. I built a receiver… to join you in the past.”

My mouth opened, but my mind stopped. I was dead.

*

I was alive, in pain, laying in a bed. Every muscle within my skin ached, and my skin hurt too. My heart cried out for sweet, merciful release.

“Get up, Feng! Get up! We have to save him! We have to stop him!”

My eyes had fallen to the bottom of a well. A dark border clung to everything in the room, which was full of blue and red ghosts, numbers and moving lines that hung in the air. At last my brain settled on the realization that I was in a hospital room. I was a patient here, though I had never seen a hospital as stark and cold as this one.

“Get up!” she cried again.

She. It was Bethany’s mother. What in the hell – No, that was impossible. Bethany’s mother died last year. She was a smoker, and –

“Get up or I’ll drag you out of here. You’ve already wasted two days. How long do you think it will take him to join the signals?” She was frantic, and she was not her mother. She was Bethany, but so old. Her lovely blonde hair, done in such an American style, was gone to iron, and her breasts. No! How they sagged down to her heavy-set waist. She began pulling small glowing coins off of my arm and chest. Her hands swelled at the knuckles and commanded little dexterity.

I struggled to get out of bed. My legs barely functioned, my hips hurt so.

“Behny, what’s happening? Is this the future?” It was difficult to speak with most of my teeth missing.

“Don’t be an idiot. It’s only the future if you’re in the past. I mean – look, Yuchen explained something called hyper-temporal physics to me through a closed door, so don’t blame me if I don’t get everything perfect. He said he wanted you to see his final triumph, but then nothing happened. He showed me pictures on his crazy machine. It took forever to get an image, and then all we could see is what you can see from this bed. He said this was the future. Is. Will be – God. Whatever. He sent me to help you come see him. I think he wants to throw a final switch or something. We have to stop him! We have to save him!”

“Stop who? Save who?”

“Our son, you old fool! They’re the same person!”

We got me dressed in some oddly-shaped beige clothes that drooped around the shoulders; or maybe my shoulders drooped. Then we made our way through the empty halls of the hospital. Sleek, advanced servoids glided by us, but paid little attention, apparently not seeing me as a patient without my little glowing coins.

Stepping onto the city street, everything overwhelmed my senses. It was familiar but profoundly changed. Glittering buildings pierced the filthy clouds dividing Manhattan from the Sun. We rode to our destination in a servoid-driven cab, listening to whiny American music and breathing in “fresh” soda pop-scented air – for a fee the servoid automatically added to the fare.

We came to a gaunt giant in Hudson Yards corkscrewing its way towards heaven. A polished plaque by the giant golden doors read ‘KronoT’ch – Founded 2043 by Yuchen Luan.’ Not ‘Qilin’s Horn Unlimited,’ as I had planned. Moreover, the plaque made no mention of me. What had Yuchen done?

A golden servoid glided up to us, and urged us to follow it inside, until we came to a wide circle in the floor, bounded by a simple railing. “You may wish to hold on,” the servoid said. We did as we were told, and the circle became a disc that rose up from the floor. We continued to gain altitude at a dizzying pace through the cavernous atrium, for, indeed, the building had to be over one hundred stories tall. A wave of vertigo took hold of me, turning my already weakened knees to electrified jelly. Bethany was forcing herself to take deep breaths and clenching her eyes shut.

“Think, Feng. We have to do this. One of us has to reset this machine.”

“I don’t… I don’t know how his machine works exactly. It’s decades ahead of mine back home.”

“You have to try. Promise me!”

I reluctantly agreed, though I had some thoughts on the matter.

The platform slid smoothly into a dock on what a sign identified as Luan Level. “Yuchen has his own level,” I said.

The servoid corrected me in a bland voice. “Master Luan owns the entire building and half the city.” It was listening to us.

We stepped from the platform into a mercifully enclosed outer office. From there, the servoid ushered us to a set of double doors. These swung open, and Yuchen stood before us.

“My God!” his mother gasped.

Yuchen was a portly man of about sixty, dressed in a black-and-gold dragon robe and cheap bamboo slippers. His face showed signs of “work” as the Americans liked to call it. The nose was not the one Bethany and I had given him, and the chin line was a mess of alterations and corrections that added up to something uncanny, ugly.

“Welcome, Father, Mother.” He said it, but he did not smile it. A son should smile a warm greeting to his treasured parents.

I looked around his office, which was handsomely appointed in rich woods and an obscene amount of golden trim – which I assumed to be the genuine metal. A baroque desk lay covered in expensive crystal tchotchkes, but there were no pictures of any wife or children, not even a dog. What I most noticed, however, was the device set up at a table in the center of the room. Well, parts of it were on the table; other insubstantial readouts circled the device at eye level. In all, this Qilin was a more impressive version of the one in the turret room back home, but it too displayed a braided golden thread that sang out its lovely tone.

“Your Qilin was a failure, Father. As were you. That is, until now. Until I used your research to perfect your project. You had the beginnings of a fine idea, but you just couldn’t push your limited intellect across the finish line.

“You have no idea how I’ve had to maneuver these past fifty years, both inventing and marketing new devices that allowed people to take a pitiful peep into the future. I had to watch all those small minds gawp through the Qilin like it was some crystal ball at the carnival. They got glimpses of themselves in their pathetic futures. They came away shocked or thrilled, I didn’t care. Those people, my loyal customers, made me so rich. How I fucking hate them. I gave them their little prize, but I also withheld the golden thread. The true power of the Qilin.

“Your visit today represents only one advance on the process. As you can see, your minds occupy your bodies as they are today. This is a special gift I do not provide to my many eager customers. They can look, but not touch their future. My honored parents get to live it.”

It was Bethany who found the words first, and they were angry words. “Who would ever want to jump into an old and worn-out version of their own body? What horror have you created, Yuchen? This is terrible. My ankles are the size of grapefruits and I’m deaf in one ear. Send us back! Send us – Oh, God!”

I looked at my world-weary wife, and then I looked at the middle-aged man who was Yuchen. His face carried the deep lines of anger that seem to come with success. There was no mirth in his puffy eyes, no sign that he smiled much or found time to laugh. Such things paint a man’s life portrait; time’s brush had rendered Yuchen’s adult image in pigments both drab and bitter.

Tears rolled down Bethany’s face. “No, Yuchen. No.”

I couldn’t be certain I was taking everything in properly, my senses were far duller than I was used to. “What? Somebody tell me is simple terms… uh… what?”

I’ve heard my share of cruel, mocking laughs, but never from my eleven-year-old boy who now stood before me as the product of half-a-century of callousness. “You’re still too slow, Father. Even this woman has beaten you to the answer.”

“This woman is your mother.”

“I don’t need a mother… or a father, Father. Do you know who I am? I’m Yuchen Luan! Yuchen Luan, the third richest man on Earth, soon to leave the others in the dust. All I have to do is to give myself… a head start.”

“No, Yuchen! Please! You can’t do this. Yuchen has a right to his own childhood. I’m his mother. I forbid you from – ”

“Forbid, woman?” Now, he was truly being mean. “You can’t believe that you have more say over that little boy’s life than I do. I am him. He is me. I am Yuchen Luan!”

He was a puzzle, all clouds. Gray and gray and gray. At last, I found the pieces coming together. A very cruel puzzle, indeed.

I’d built my Qilin to spy on distant tomorrows. The idea was to seek out my own brainwaves in the future and peek through my own eyes to see what I could see. The potential for discovery was enormous. I would win the Nobel Prize for Science and buckets of other shiny medals. All of that fame and fortune had blinded me to the other potential use of Qilin. Yuchen – this, older, more jaded Yuchen – had worked with my process and seen the other possibility. He meant to transfer his whole being into his younger body, taking his future knowledge with him.

“The light’s come on in your eyes, Father. If only you’d shown any sign of such intelligence years ago, I wouldn’t have had to watch you drag our family into bankruptcy. I sorely wanted to tell you I could fix your machine, but that took years and years. I did make it work, just as you intended, but by then you were a broken man, living in one asylum after another. I supported Mother and Elsbeth.” He walked over to a trophy case packed with tarnished cups and statuettes and tapped on the glass. “I worked and made something of myself. I discovered it was possible not only to peer into the future but to jump into the past and add decades to my life. All thanks to your prototype and the signal it put out for only a few short weeks. Young again, and with a unique working knowledge of the Qilin no other human being possesses, I will reach new levels no one dared dream of. Once I gain full control over the system, I’ll sell tickets to the special few. By the time I’m twenty… again… I’ll own the whole damned planet!”

“No,” his mother pleaded.

“And when I get old, I’ll do it all over, moving technology forward with each leap back. Again and again, always learning, always young!”

Bethany was sobbing. “I want my baby. Please! Look at you. Don’t you see how hollow, how fragile you are, with your boasting and your huge office. You did this to yourself. By tampering with your own childhood, you’ve robbed yourself of resilience and hard-earned strength… and hope!”

“Enough!” Yuchen shouted.

Now I stepped up, drawing myself to my full height, causing my lower back to issue a dry cracking sound. “You will treat your mother right! You wanted us here for a reason. You wanted me here so you could show me how superior you are.”

Yuchen narrowed his eyes and smirked, a chess-master with his fingers on the winning move.

“I’ve accomplished that, have I not?”

“No,” I said. “You haven’t. Not yet. Yuchen, I will fall at your feet and praise you, if that’s what you want. First, you have to give your mother what she wants.”

“Give back my childhood into her pathetic hands? I don’t think so.”

“This machine. You haven’t keyed in the final link, have you? You called me here specifically to witness that, right?”

“True. The Qilin is attuned to both my selves, but the link is a tentative one. I have control for now, but to make it permanent, I must allow my young self to return in order that I may shove him into the void entirely. The boy I was must cease to be, then once I control that body in full, this aging frame will be vacant – to be taken out with the trash for all I care. The real me will return to the bountiful past with a mind full of priceless knowledge and experience.”

“And no joy,” Betheny added, though goading Yuchen did little to help the situation.

“Yuchen, let your mother see her baby. Send her home and let her hold our son one last time.” I begged him further to allow me to speak with Bethany in private. He agreed and we stepped briefly into a side chamber of his office suite. I explained as quickly as I could how she might reverse the signal that had send me forward and pull me out of the time-cheating recliner. Once that was done, I promised to sever the link entirely. Without a receiver in our present world to boost the signal, I hoped, this older Yuchen would be trapped on his side of the rift. “Then, I can get to work building in safeguards to prevent him from trying this again.” I reassured her with a firm grip on both shoulders. With the safeguards in place, I could move ahead again with my work. In fact, I’d gained years’ worth of advances, so success was closer than ever.

We returned to Yuchen and his Qilin.

“As you can see, this version of the device needs no headset. Mother, you are in luck. It will take me a few moments to prepare. In that time, your Yuchen should return for a final appearance. I will take his place shortly thereafter and permanently. You have until then to do whatever it is mothers do with backward little boys.”

With a few gestures that barely grazed the Qilin’s surface, Yuchen made good on his promise, but he did so in a careless manner. The result was terrifying. By suddenly ripping Bethany out of her older body, he damaged whatever consciousness occupied that frame. The withered woman standing next to me collapsed. Her breathing became labored, and I could not rouse her.

Looking at the figure on his office carpet, Yuchen said, “She was quite senile, Father, before the Qilin brought her younger self forward. Now, this person is once again a doddering fool.” This person was his mother. “It doesn’t matter. No one will miss an old woman. I suppose you’d like to join in the emotional moment.”

“Yes!” I very much wanted to get back to my turret room, my Qilin, and my son.

“The interval when the boy is present will be brief. I have only a few adjustments to make before I leap in permanently. So, I will allow you to see, though not be in that time. I’ll keep the real you firmly rooted here and monitor events through your eyes.” He pointed to a hovering blue concavity. “Should anyone try anything, the result will be most unpleasant.”

“You don’t trust your own mother?”

“No, which is why my Qilin is fully in control of your Qilin.”

He had heard us earlier. It was no good arguing.

Despite the exchange, he again gestured in the general vicinity of the Qilin. I fell off a high cliff. My awareness dropped a thousand miles, though there was none of the sensation of falling that usually assailed the pit of my stomach.

Suddenly, I existed in two very different realities simultaneously. In both places, I was seated, but while my older self could move somewhat, my familiar, younger self was all-but frozen. I therefore retained my view of older Yuchen’s office while at the same time receiving a fixed view of the turret room from the patched recliner.

Part of me was there in what I believed to be the present. There, my eyelids opened a sliver, but I could not move my hands. Off-center from my focus, I saw Yuchen. The boy was screaming in fear. Screaming like any terrified eleven-year-old boy might under the circumstances. I couldn’t imagine what it must be like to be shoved out of your own body, stuck in some dark corner of your own mind… and have it done by yourself!

Bethany was frantically searching the clutter of the turret room. I couldn’t quite understand what she was saying. The words were right, but my brain couldn’t quite process them. I did manage to snatch two syllables: “Sorry” but without context. This was a lousy connection. Bethany was calling, for help I think. Elsbeth appeared at the door, carrying Yuchen’s aluminum baseball bat. What an odd time to play ball, I thought.

My bifurcated mind was not working at peak efficiency, but it got there. The conclusion was as subtle as the bat slamming down on the Qilin.

In the past, I cried out in horror! “My creation! Stop stop stop!” Nothing came out… then. In older Yuchen’s office a half-century later, I actually screamed so loudly it unnerved him, and he stuffed a cushion in my mouth. The me in the turret room had no choice but to silently witness the destruction of my lifelong dream. A tear may have trailed down from my eyes.

Chaos wailed its dark cantata.

Little Yuchen cried out in blind terror. Old Yuchen bellowed in naked, deranged fury, clutching two trembling fists to his temples. He stumbled about the room madly as his eyes rolled back in his head so far nothing but the whites showed. A searing howl filled my ears then swept off into the distance like a train whistle and vanished. Fifty years away little Yuchen’s tantrum eased to a dull, snotty sobbing. I saw his brilliant boyish eyes clear and look at me. My boy.

Bethany swung the bat. Elsbeth cheered her on. Both my selves screamed, one silently and one aloud.

The two realities overlaid one another until…

Darkness hushed my worlds.

*

When I came to my senses, my unified senses, I found myself back in my older frame and only there. As poor as my vision had been in the past, it was worse now. The myopia and a steady tinnitus kept me from grasping things as quickly as I might have. I saw old Bethany, curled up like a kitten, but breathing, for what that was worth.

I was distracted by several servoids mulling about in circles, their facial screens flashing red. I looked around. All of the doors of the office suite were open, affording a view out to the cavernous atrium. At the dock where we’d arrived, more of the servoids stood, regarding a single bamboo slipper near the low balcony rail.

My boy.

I looked back to the Qilin. The floating readouts had evaporated. Parts of its matrix had gone dark, and thin whisps of smoke rose from its ruined innards. The main display was still working, but what I saw filled me with dread. The golden thread was no longer an infinitely sublime braid, nor did it emit a splendid tone of quantum triumph. Instead, chaos ruled the face of the maimed device even as it wailed a staticky lament.

Here I was, and here I’d stay.

My feet hurt.

*

Somewhere, in a place outside of time, a magical horned creature was enjoying a good laugh.

###

If brain-scrambling stories about time travel are your thing, here's one you'll love:

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Butcher-Chris-Riker/dp/B0D6PT9KX6/

- Details

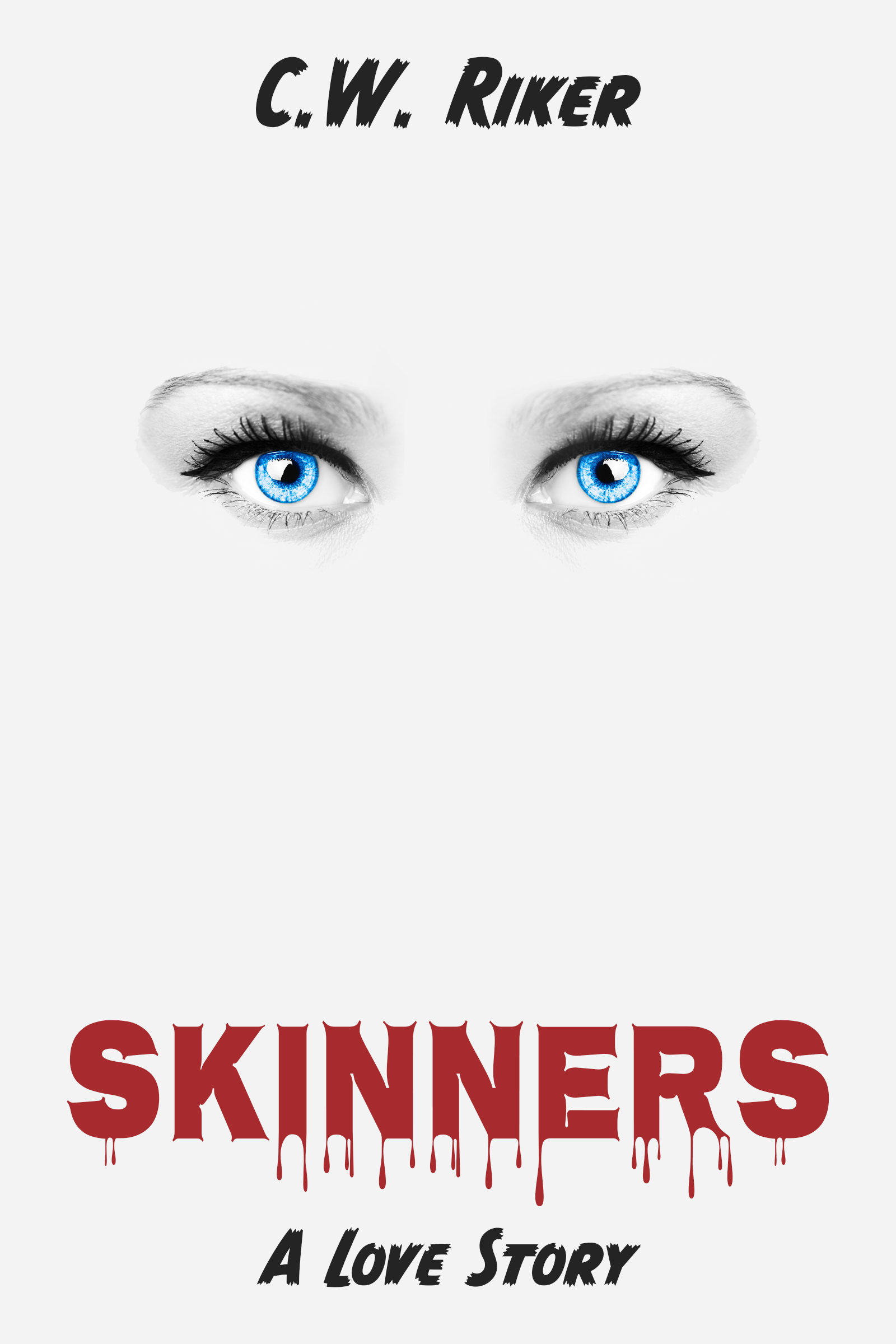

Think you know your werewolf from your vrykolaka? Take a look at various shapeshifter legends from around the world. Then take a good look in the mirror to make sure you're still you!

https://mythicalrealm.com/mythical-creatures/shapeshifters-around-world/

If you enjoy shapeshifters, Skinners - A Love Story is just the tale to chill your blood. Check out a FREE preview:

https://chrisrikerauthor.com/news/short-stories/they-love-you-they-want-to-be-you

(Special thanks to Susanne Allen for the cover design!)

- Details

After they’d spent precious hours running like ponies and grinding red clay into the seats of their blue jeans sliding down the hill, Bo asked his mother, “Can we do this again tomorrow?”

The wild-haired girl, three inches taller than her son despite being only a few years older, answered him with patience. “Probably not. If I had been a better saver, we could, but no. This is why you must save up now. Trust me, you’ll be glad you did when your days turn hard.”

She chose her words carefully whenever she explained things to him, now that he was old enough for banking.

“Eat your grilled cheese sandwich. I fried the bread with lots of butter, so it’s greasy and full of wonderosity for your tummy! I think,” she said, checking the fridge, “yes, we have sweet baby gherkins!” She unscrewed the jar lid and plopped two fat ones on his plate. Mom knew what he liked.

“Awesome!” he shouted, crunching one with his mouth open, spraying pickle bits everywhere.

Her smile faltered as she talked about her own mother spoiling her with special treats from her magical kitchen. Pappy would swoop in and swipe some. It made him so – All of a sudden, her eyes moistened. Girl-Mom said Grammie’s funeral shattered Pappy. She wanted to cry too, she said, but could not. Then, weeks later, she cried and could not stop. “I wish my mom was here in this kitchen with us, three small children laughing and getting into trouble. She’d have loved that.” Mom wiped at her eyes before any tears could escape.

Bo gave her a moment then asked, “When can I see you again, Mommy?”

“Soon, Bo. Soon.”

Bo looked disappointed for a moment. He loved his mother when she played with him this way. He wished Dad would join in, but Dad had to go to the hospital. Dad wasn’t sick; that was Mom. Dad was quiet when he was home. He didn’t talk about Mom, and he refused to play with her when she was home from the hospital and little. He said it was… how did he say it? “Paying for daydreams, but, if it makes you happy, darling…” So, they saw very little of Dad.

Bo missed Mom on the days when she was only big in the hospital being “very sick.” His dad said Bo would visit her there soon, but that he shouldn’t think about it, “shouldn’t remember your mother that way.” How could Bo not remember his mother one way or another? It made little sense.

He would remember his mother after today, just the way she was: right there in their kitchen, stretching herself as tall as she could to reach into the high cupboard and get the Oreos. Of course he would remember this moment; just as he remembered her visit last week, when she was a young woman fresh out of college, talking a mile-a-minute about all the things she’d just learned; or remember the week before when pubescent Mom giggled about her tiny new breasts, “so cute and firm.” He didn’t understand her shameless, pink-cheeked whimsy, but she was happy, and that made Bo happy too.

“I wish I’d saved more of these, Bo.” As she said it, his mother’s face darkened just a shade, with the kind of expression that didn’t belong on the face of a girl of twelve. “Save. Save. Save. You’ll thank me later. Oh, but there I go again, wasting today on thoughts of tomorrow! I have three more hours left. Finish your sandwich, and we’ll run down to the pond and catch tadpoles. I won’t be around, but you can watch them turn into frogs. It’s gross – perfect for a boy!” She poked at his side and made him squirm and squeal, and she joined him in making silly, kid noises.

They spent the next hour catching tadpoles in a bucket and decanting them into the old aquarium in the garage. The hour after that they devoted to smashing toy race cars into each other. The third hour, they sat on the back porch holding hands, drinking Cokes, burping, and staring at the sinking sun. It was a perfect day.

On Mom’s advice, Bo banked a whole week. To his disappointment, when he looked in the bathroom mirror, he couldn’t see any difference. He was hoping he’d find a mustache, but no. He was still nine-and-a-half, no mustache. His mother had told him this was the best way to save, a little at a time. “You’ll be happy one day,” she said.

Bo’s father made him breakfast – a Pop-Tart and some orange juice. “I have to head out, kiddo. I just talked to Maria,” he said, holding up his phone, “and she’ll be here in a few minutes. You be good to her. No back-talk.”

“I don’t like Maria. She never plays with me like someone my age.”

“She can’t, Bo. She grew up in a poor family. I explained this all to you.”

“I know, you gotta have money to do banking.”

“Yes, uh, that’s about right. Look, I gotta get to the hospital. The doctors say –” His father stopped himself and stood there silently with his eyes closed. Dad looked like he hadn’t slept well. He always looked tired these days. Bo wished Dad would use his kid days. He wished he’d stop worrying about money and doctors and dumb grown-up things. Dad said that growing up his parents only had a little money, so he didn’t have “much time to kid around.” Bo got the sense Dad didn’t like banking, but he always told him, “We have the money, Bo, so you can save up like Mom did. It’s your choice.”

His father hugged him very hard and very long, then left and drove off. Bo spent the day with Maria, who made him work on fractions. He hated fractions. He just wanted to go out to the garage and see whether his tadpoles had turned into pollywogs. He wondered whether rich frogs went back to having little stunted pollywog limbs some days. He hoped they did. He’d find out.

Bo missed his mother. His father was taking a “sabbatical” from his job at the college. They were living on savings. That meant his father could go to the hospital to visit Mom every day. It also meant his father could enjoy his yucky drinks every night in front of the big screen, watching his favorite vacation mem-vids of him and Mom in Ecuador, Morrocco, and Queensland. They’d loved to travel when they first got married.

The next day, Bo’s father took him to the hospital to see Mom.

She was thin, very thin. Things stuck out of her arm and her face looked narrow and sad – sadder than he could ever remember her. Bo couldn’t see the little girl in her at all.

His father stopped a doctor passing in the hall, and they traded hissing words. Bo didn’t understand all of it. He caught “are you sure all this projection and recall isn’t making her worse?” and “working the way it was intended” and finally, in tones even more hushed “not much longer now” Bo tried and tried not to remember that last bit.

“Just for a moment,” Dad said. “She’s awake.” He was glad his father had told him that, because when he looked, he wasn’t sure. “Tell her that you love her, Bo. Tell her nicely, like a good boy. ‘I love you, Mommy.’”

Bo didn’t want to say the words. He didn’t know why. He certainly did not want to get any closer to the woman in the bed. Every step closer screamed, Mommy looks wrong! This wasn’t the girl who taught him to tie a necktie, or the fresh-faced woman who explained to him that what women really want is someone who’ll listen and that he needed to learn to do that when it came time for him to date, or the wet-eyed twenty-something who tried to explain that funerals were a farewell party for people going to a better place. This was NOT Mommy!

“Go, Bo. Please. Just get close and say, ‘Love you!’” His father was on the brink of panic.

Bo was already closer than he wanted to be. “I love… you… Mommy.”

His mother’s eyes focused in that moment. Her face turned ever so slightly in his direction. The barest flicker of a smile lit her face, the barest semblance of the Mommy he loved to play with. Then she closed her eyes.

A monitor on the wall bleeped, and a nurse came in. The monitor was one of two very different kinds of devices in the room. The other, a slender passbook sitting open on a bedside table, showed two bright tally pages. The page on the left in amber showed a low number. The one on the righthand page had a 1 glowing in Incredible-Hulk-green. The nurse checked both devices, looked at his father, and told him and Bo it was best if they left for now.

That night, Maria watched him while his father stayed at the hospital with his mom. Bo looked at his own banking passbook, the one his parents had bought for him. The left page was blacked out. They’d set it so he couldn’t check that number. The right page showed a green 17. He had 17 days saved up. For reasons Bo could not put into words, he felt that was a very small number.

He picked up his passbook, decided on a number, and keyed it in just the way they’d taught him.

The next morning, his father stopped by for a shower and change of clothes. He didn’t bother shaving or tucking in his shirt. He was just headed out the door when Mom arrived.

There she was, in the living room, Mom as a nine-year-old girl.

“Lana?” His father struggled for the word, as a diver trapped under the ice might suck in a last pocket of precious air. He stared at her, through her.

"Don,” she cried, hugging him about the waist.

He stood, blank-faced, his hands hanging awkwardly by his sides. “I never knew you like this.”

“It’s so wonderful to be nine again, just when I needed it most. I always imagined I’d end up spending these days alone, skipping rope and picking daisies. Instead, all I want is to share these days with Bo.”

“I’d hoped, maybe you would have saved a day from when we –”

“It’s my last day. I saved this day just for today. The three of us can –”

“No! I have to be with you – with you at the hospital.”

Bo watched Dad leave as if ghosts were chasing him.

His mother turned to him. “What would you like to do today? Would you like to check on the tadpoles?”

“No. That’s silly,” Bo said. “Kid stuff.”

She looked him up and down. “Good thing we’re kids then, right? Let’s do nine-year-old stuff.”

“I’m eleven.”

“Bo-Bear, you’re nine. Well, nine-and-a-half. I think I know my own son’s birthday.” Her pretty blue eyes shaded over with concern. She looked at him more closely. “Wait. Your face! Your pant cuffs! Are you taller? It’s so hard to keep track when I keep changing height. Bo – Bo-Bear, what have you done?”

Bo hesitated, then explained that he had squirreled away a big chunk of his childhood so he could enjoy it when he was old. He said, “We’ll have loads of time to play and do fun stuff, go for hikes and play games and... and please don’t call me Bo-Bear.”

Mom’s jaw dropped open in a way that the jaws of seven-year-old girls did not. “Honey, don’t forget the tadpoles. You can do all those other things, and you will. I can’t be with you for that. You need to find someone…” The words choked in her throat. After a moment, she said, “someone your… own age.”

Maria came by and took them out for pizza but mostly left them to themselves. The morning cloud passed, and they spent the day talking about dinosaurs, and Mom taught him to make a big wet fart noise by pressing the palms of her hands against her mouth and blowing. He laughed until he thought he’d pee himself. It was magical.

Just before she left, Mom asked Bo, “You know what? Don’t bank too many days. Maybe even hit clear. I’m not sure how that works, but maybe…” She paused, drawing in a deep, jagged breath. Mom took her boy’s hands, smiled her biggest smile – she was missing a front tooth – and looked into his eyes. “Spend your days, Bo-Bear. Every one. Burn em bright as the sun!”

Her face beaming at him turned his insides all funny, a lot happy and a little sad, but it was a perfect day.

One of his very best.

***

As Bo grew into a teenager, his father never showed up as a boy or teen or young man to play with him. Dad showed up often, as Dad, and did what he could to fill the void in both their lives. He said he’d cleared his banking account. He would never say what numbers were on the amber left page or the Hulk-green right; insisted he never even thought about glowing numbers. Bo thought carefully about that while looking over his own passbook.

Sometimes, they would eat grilled cheese sandwiches and watch the mem-vids from Queensland. Dad showed Bo the time Mom got to hug a koala. The newlywed couple acted like they had a baby, bouncing it and dancing around in a circle to some unheard melody. In that special moment, she was a happy woman-child.

“That’s you when you were a baby koala!” Dad teased him.

Bo and his dad chuckled at the silliness, and, from some secret place within him, Bo could hear Mom laughing along.

###

Thanks for checking out my little story. I hoped you enjoyed it. If you did... please take a look at my novels. Here's a couple you might enjoy!

https://www.amazon.com/Goody-Celeste-Chris-Riker/dp/1665307072/

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Butcher-Chris-Riker/dp/B0D6PT9KX6/

- Details

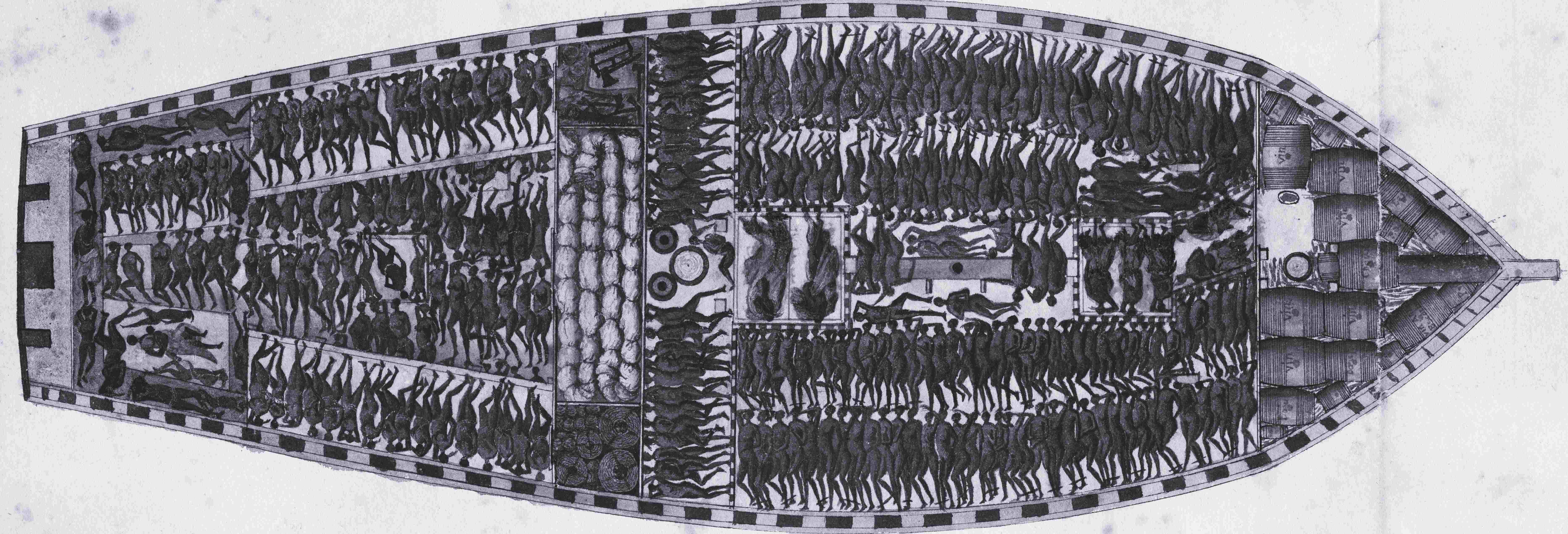

In my novel, Darkling - An American Hymn, one such slave comes to Newport in the care of a demon, Orv, who tells her how lucky she is.

Adaeze must fend off Orv's perverse worldview, survive her bondage, keep her daughter safe, and ultimately decide her true place in the world.

https://chrisrikerauthor.com/news/short-stories/can-the-future-overcome-the-sins-of-the-past

- Details