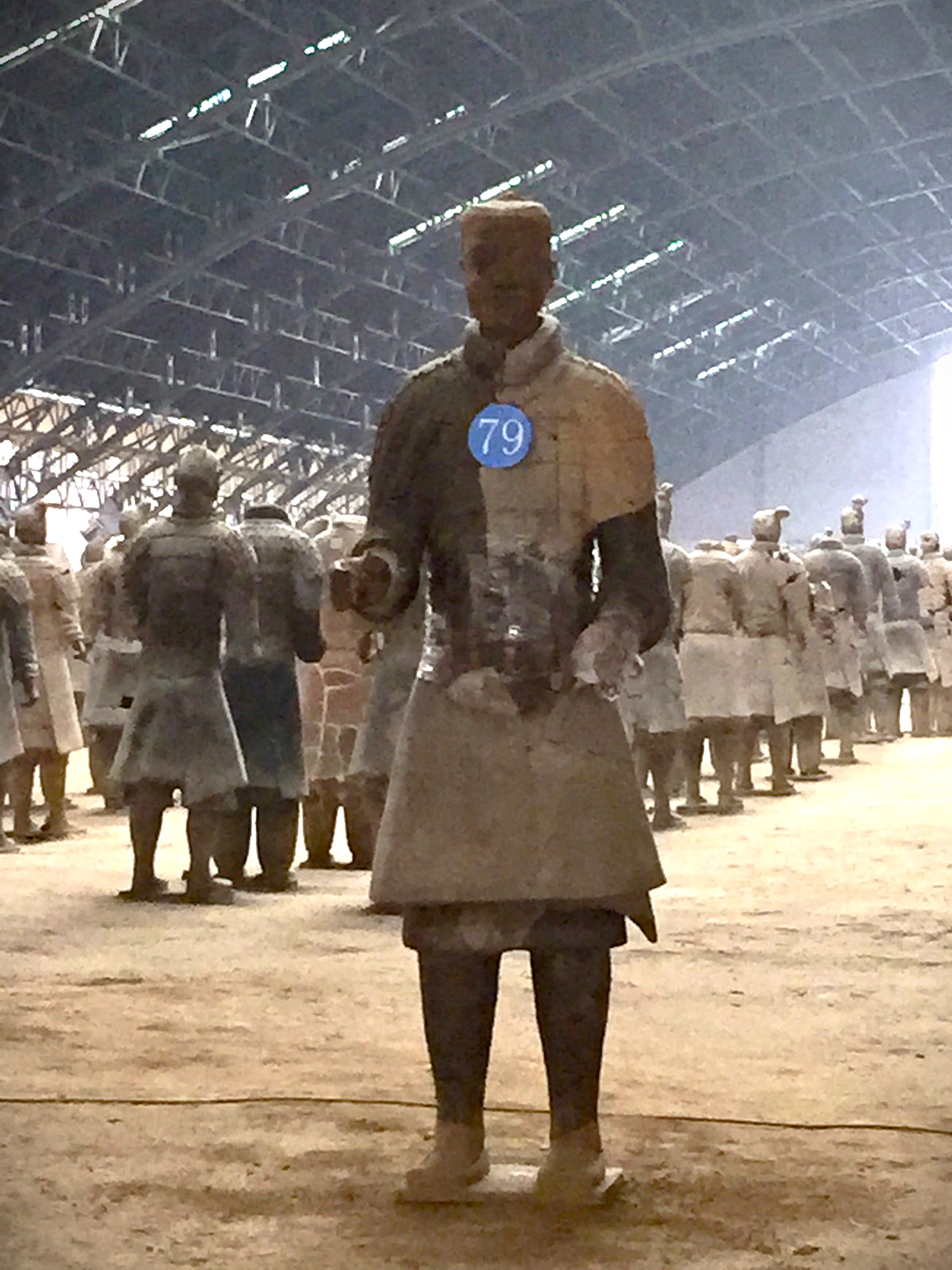

(BTW, the pics on my site are from our trip to Xi'an to see the Terracotta Army. This display is truly breathtaking!)

When Chinese archeologists began digging up the Terracotta Soldiers in the 1970s, they were horrified. They watched helplessly as pigment exposed to sunlight after thousands of years faded in a matter of hours. Resolving not to make things worse, the government decided not to open Emperor Qin's burial mound -- reputed to contain an entire necropolis -- until such time as scientists could ensure the artifacts can be protected. It's a painstaking process to learn the secrets of this enormous site and its thousands upon thousands of soldiers. In my novel, Zebulon Angell and the Shadow Army, our hero goes marching straight into Qin's necropolis... and meets Qin! In China today, scientists are working to learn all they can. Here's the latest:

https://allthatsinteresting.com/terracotta-army

Check out what's really in the emperor's city of the dead, in Zebulon Angell and the Shadow Army.

Paperback (cheap!!!):

https://www.amazon.com/Zebulon-Angell-Shadow-Chris-Riker/dp/1637107056/

or Kindle (even cheaper!!!):

https://www.amazon.com/Zebulon-Angell-Shadow-Chris-Riker-ebook/dp/B09P8TJZ4Y/

- Details

Somewhere near the imaginary line of Mars’s languid 687-day orbit – it hardly matters exactly where at this point – one might find a chamber that briefly contained the most desirable of all knowledge.

***

Between Sol and the infinite travels a sizeable, icy mudball, far from home and destined to go much farther.

***

In the center of First Town stands a ten-foot obelisk rendered from native stone, somberly dedicated to the better nature within us all. It is not a statue, though some say it should have been.

***

The angels look on in silence.

***

“Lay on more sail! Mind the mizzen topgallant! Step lively, or I’ll throw you to the maelstrom!” Li Dongsheng cried to his operations chief. She giggled.

Skipper Dong was happily miserable. The ship’s surgeon had diagnosed his malady as acute head enlargement, Maotai Baijiu variant, not that anyone begrudged the old man his remaining pleasures. He squinted in the glare of the morning Sun on the main viewer, morning being a term applied out of habit to the large fusion reactor ball hanging 130 million miles aft. He was a proud Chinese man of 72 years out among the mute titans of the void, equal to them, a transient status that made him miserably happy.

“We have no sails, Skipper,” she said in a flat tone, not wishing her words to sound mutinous to the rest of the personnel on duty in command-and-control. Neither did she want to admit that she had no idea was a mizzen topgallant was.

He bellowed, “You’ve lost our sails in the tempest, Mr. Thandi?”

Operations Chief Thandiwe Gaines giggled whenever the old man called her “mister.” No one else aboard dared raise a little girl’s giggle from the 32-year-old officer. If they tried, she’d break their arm. Skipper Dong was a beloved exception to most rules, even his new title, adopted at their launch. She hadn’t the heart to tell him it should be Skipper Li and that Skipper Dong sounded like a grape she once picked as a child growing up in Duluth, Georgia. It was a fun memory. Scuppernongs were gone, along with so much else.

“No, Skipper. Tianlong’s manifest lists no sails at all.” Rather, they were screens, energy fields soon to come alive amidst a vast webworks in space. She’d gently corrected the skipper a hundred times; it made no difference. Most of the crew called them sails now, and she felt herself slipping into the habit as well. Eccentricities aside, Skipper Dong’s was the mind that designed this vessel and even coined the term “screen” before succumbing to the rapturous romance of the deeps with its colorful lingo.

“You forgot to requisition sails? You’ll walk the plank!” She barely weathered his pronunciation of Ls and Rs without snorting.

The other command crewmembers of first watch tended their stations, stone-facedly ignoring the exchange. “MLF: viability of fusion reaction within magnetic containment, as usual, but all indicators are nominal,” Third Officer Forsyth read from a screen that updated constantly. Several other mundane items hovered near the top, all green. MLF was Most Limiting Factor, the thing that needed attention soonest, but this morning nothing was on the verge of breaking or running out. Forsyth liked to joke how the acronym MLF reminded her of something dirty from a century ago. Forsyth was an authority on historical filth.

Hamza rolled his eyes and sipped his aromatic Cardamon. The crew typically used bulbs for drinking to avoid spills. Not Hamza. Thandi never looked him in the eye. He’d been weaned on petroleum or rather the oceans of wealth it produced while turning the Earth’s atmosphere into an oily shroud. His family had used its money to get him into the finest business schools in the European Bloc.

“Your tatami boat is running well, is it?” he said off-handedly.

The hull of the Shuang Tianlong, which the crew shortened to Tianlong, ignoring the intermingled bliss and terror inherent in all mated pairs, included an outer woven layer, made of bio-engineered bamboo. It was one of the few crops that could still grow in the filthy atmosphere of Earth. It had the tensile strength of carbindium at a third the weight, and filtered radiation. Weaver bots crept tirelessly along the two hulls. Upon finding a worn or damaged section, they unspooled soft bamboo strips from within their spider-like bodies and wove them into the hull’s protective sheath, returning to resupply from the ship’s aeroponics units as needed.

Hamza’s tatami comment wasn’t too far off. The problem was his contribution stopped at unsolicited comments. He never did any real work. She found his smokey-sweet, lemony-scented tea vile, along with the man drinking it.

The old man went about his morning business, standing beside one officer then the next, chatting and checking. He ignored Hamza’s snide remarks. The skipper was in his element. Reality be damned! What need did he have for harsh reality when dreams were within his grasp.

It would have been nice for Yuxuan to see this side of his father. Yuxuan. He should have been here now. Thandi reached out two fingers, penetrating the tiny holo-pic hovering at her duty station. It showed the two of them sailing on the Grand Canal in Hangzhou. The effervescent edges gave it a certain quality, a dream within a dream. The feeling was fading somewhat – no sharp pain, merely a too-familiar longing, the dull throb of a young heart missing its playmate.

“Da bao,” she mouthed. His face always got red when she called him the baby – he said it reminded him of the time “when I was very small and tried to pet the koi fish, and Father beat my bottom into raw pork.” After that, Thandi teased him mercilessly, transmuting pain into playfulness until he began to let go of useless guilt. She wished he’d have let her do more for him. Yuxuan always carried the weight of the world. Like his father. The angels should have talked to both men, but angels hold their tongues.

Stop. Back to business.

“Raising sails,” Thandi complied. Screens, sails. The skipper never played his mental games in such a way that would confuse the ship’s orderly operation. Pilot fish drone cams provided external views of the ship from several miles out, occasionally swinging around to check on the other vessels in their convoy. These ships still depended on their conventional propulsion motors, while Tianlong’s had shut down.

Soon, the pilot fish would have to scurry back to their docks or be left eating Tianlong’s cosmic dust. The changeover had begun, power to sail.

The command-and-control crew watched the monitors as the sail matrix deployed its molecular carbonite lines (MCLs). They would eventually stretch for tens of miles, literally diamonds in the sky, folding out into powerful wings. The lines twanged and sang their oratorio, which resonated deep inside the ship, while the angels who lived in the vacuum of space heard nothing. Silence worked both ways.

Latching arms joined Tianlong’s bifurcated ovate hull, leaving ample deck space amidships for the MCLs’ storage and deployment mechanisms. Thandi had always thought the ship’s profile looked like two gargantuan beetles with finely woven carapaces. As they embraced – naughty beetles! – they stretched out their elytron and underwings. The MCLs shot out in multiple directions, spreading like some impossibly precise nets from a trawler.

They weren’t netting fish but rather cosmic super-speeders. And they could hardly catch the busy little packets of energy, but they could get in their way, using fields projected on the “sails.” Once they began to unfurl, the great weave of the hull gave out with fibrous whispers, creaks, and snaps like some cyclopean wicker basket. The hull dutifully accepted the load, actually drawing strength from the stress. The “fireflies” as the skipper called them would surrender the tiniest fraction of their vigor, filling the sails and boosting Tianlong on her way.

Skipper Dong regarded the scene carefully, checking the readouts as they clicked off the proper metrics. Tianlong’s Nao, the brain safely secured in a deep chamber, handled all variables instantly, drawing obvious admiration from the skipper. His fingers traced the outlines of his vessel. “Like bonded dragons, mated for life.” Skipper Dong mused, “They are of opposite natures, one warlike and one nurturing. They battle for dominance but make love without shame in the starlight.”

He looked to Hamza and offered a perfunctory smile, which went unreturned.

“Set course due west!” the skipper ordered.

Thandi keyed in her verification, allowing their reclusive friend Nao to accept the command. Her duty station came alive with a flickering of readouts and cheery tones, which she found vaguely creepy. “Confirmed. Due west, Skipper. Straight for Mars.”

***

All good, Hamza said to himself. Let Li enjoy his play acting. The sooner he and what remained of his senses parted company, the better. Li’s pills were of reduced strength, just as Hamza had ordered. Everything was falling into place.

Hamza headed back to his cabin aft and took the lift down several levels. Someone had decided to display fine artwork on the bulkheads and place tiny jade or cinnabar or bronze artifacts within carefully lit sconces. The air on this ship smelled like someone’s garden rather than the ozone-and-body-odor climate of an Osman Consortium vessel, and there were no fluctuations in the gravity orientation field to give him vertigo. Jade Crane’s R&D unit had raised Tianlong’s life support systems beyond mere support. It was another reason to move carefully. Jade Crane’s R&D should have been his already, agreement be damned, but when his agents had stormed the complex, they’d found an empty shell. The computers were fried, the labs empty. The developers had scattered.

Hamza passed Li’s locked sanctum, a luxury suite with adjoining cabins that could not be entered from any passageway but only from the skipper’s quarters, the prize within the prize that was this ship. All the answers he sought, all in one place. If his spies were correct, Jade Crane had found the Mecca of science. Only a few inches of titanium-reinforced carbindium bulkhead stood in his way. Expecting nothing, he brought his cuff near to the lock. His people were feeding constant updates to the cuff, trying to hack through Li’s security. The fist-sized sentinel on the bulkhead chirped and buzzed a rebuke.

“How are you keeping me out, Dongsheng?”

Tianlong would provide a solid foothold on Mars. (Hamza would certainly change the name of the ship soon enough; “Marengo sounded right,” he had bragged to an attractive junior executive one night in his bed.) All colony ships brought personnel, habs, equipment – diggers, smelters, super-compactors, and the like – plus frozen livestock embryos and supplies, ferrying it all to the surface in a tedious succession of shuttle sorties. Tianlong was the first sizeable vessel designed to land its expansive bulk on the surface. It would then deploy its servile units to dig underground cities, extracting all the materials needed from Mars itself.

In a matter of months, they would carve out a capitol large enough to house millions! At that point, all nascent attempts to colonize the Red Planet by myriad lesser powers would fade into insignificance. The conquest of Mars by Hamza and Osman Consortium was all but assured.

Any resistance would be pacified via the shock troops currently traveling on the personnel transports alongside Tianlong, headed to Mars. “Bloodshed was the cost of doing business,” Hamza had said at Osman’s pre-launch board meeting. “The trick is to make certain the right blood is shed.”

***

The sails that were still extending along Tianlong’s midline now resembled a flower in an ancient stop-motion film meant to delight children. Offering a pinkish white luminance never before seen in the solar system, the clusters bloomed into chrysanthemums of energy and motion. Spars tightened, growing steadier with the load, a valiant array created to take the night wind and run with it. Shuang Tianlong naturally had the wisdom of two dragons. Her Nao measured every angle of every spar, checking load and tolerance from one nanosecond to the next, going faster and faster, and then fastest. The personnel transport ships packed with Osman loyalists dropped back into the darkness, unable to keep up.

For many hours, Tianlong meticulously maintained the course that would take them into Mars orbit, as their announced plan suggested.

There, she would join the scores of other colony vessels, representing the twenty-eight corporations and alliances competing – often violently – for control of Mars. Osman Consortium had brushed aside a weaker capitalist syndicate to lay claim to Mons Olympus – as big as the Free State of Arizona and a vertiginous sixteen miles high – along with land a thousand miles in all directions.

And then, at the precise time keyed into her systems, Tianlong adjusted her lovely budding spars ever so slightly.

***

Li, Skipper Dong, was an old fool. His dead son’s fiancée was no match for Goran at this vulgarly-named game of Crusades. From what he’d observed of her, Gaines would have been a good match for Yuxuan. Neither understood the use of guile. This failing had cost Yuxuan his life. Now, it would cost this girl the secrets held inside Tianlong.

A small crowd had gathered in the ward room to watch the match. Hamza could not help smiling to himself. He knew the chess-like pieces and how they moved, but the stratagems remained elusive. The relationship between pieces was difficult to see, obscured by sylvan glades or dire swamps added to the battle board for dramatic effect. Pieces moved and killed as ordered. In this regard, the queens were the most entertaining, but it was gratifying to watch Goran’s rook meet Gaines’s knight.

For a moment, both pieces met in one sector defined by vague grid lines that replaced the black and white squares of conventional chess. The sector, part of a desolate plateau, split off and hovered above the battlefield. Tiny onyx soldiers scurried about the rook’s crenelated parapet and fired their arrows, piercing the hapless horse’s neck. It screamed piteously. The knight, with no fewer than a dozen shafts now penetrating his armor and flesh, lingered a moment, offering a prayer to the silent heavens before succumbing to his wounds and falling from the saddle. At that point, the sector flew over to Goran’s side of the table and unceremoniously dumped the knight and his horse. They joined a graveyard of decapitated pawns and a bishop who’d been crucified upside down. The sector then returned its victorious rook to the correct coordinates and settled back into the board.

A blood stain (one of many now on the board) marked the engagement. This bit of drama meant nothing to the outcome of the game, but it added a certain visceral thrill.

“You move cautiously,” Goran chided Gaines. “I will have you mated in three moves.”

He talked too much. He was highly recommended as a security chief, but he should know better than to engage an opponent.

Gaines did not flinch. She said, “Unless…”

Hamza puzzled over her next move. “This game is ridiculous. Out of date, even with the animatronics to liven it up. I prefer a straightforward duel on the combat practice range on Epsilon Deck.”

The girl ignored him. She positioned her remaining bishop four sectors diagonally from Goran’s king. “Check.” This was such a stupid gesture. Goran wasted no time ordering his pawn (a pawn!) to move a single diagonal and engage the bishop. Again, the battle sector rose, briefly holding two pieces. The pawn, small by comparison, held out a rotting turkey leg for the bishop, who inexplicably took and devoured it with gluttonous zeal. The bishop’s face immediately broke out in pox. A moment later, his flesh melted from a skeletal frame recognizable at last only by his pointy samite hat.

Even before the sector had removed and dumped the dead bishop, Gaines had ordered her next move. Her white queen charged, yelling like a warrior the length of the board and dispatched Goran’s queen with daggers and cudgels. The once beautiful onyx queen offered weak resistance, finally ending her reign in a bloody mass of indignity.

“No!” It was Li who spoke sharply.

“You would do this?” His eyes were fixed, his lips pursed. “You would do this? Good.” Goran’s voice was steady. What had Hamza overlooked? Goran had just lost his queen. Why was Li displeased and Goran offering a blessing. “Very well.”

The onyx king turned to the samite queen and then casually stepped sideways one sector to join her. What he did to his enemy’s bride was unspeakable, even for tiny automatons. Her screams went on for nearly a minute before the grinning onyx king choked the final breath from her tiny body.

Li closed his eyes. “To exchange queens is wasteful. It lacks nuance, grace.”

Thandi grasped her almost-father-in-law’s hand. “Sometimes, it is necessary.” She looked into Goran’s eyes. “Check and mate,” she said as her remaining bishop closed the gap. “You should have castled ten moves ago. It’s a wise precaution. Or is caution a weakness?”

Goran should have been furious, or at the very least he should have demanded a rematch. Instead, he watched the onyx king remove his crown and fall on his own sword. He thrashed about melodramatically for a time, then lay still in a tiny red pool. “I have never seen that exact stratagem. Where did you –” His eyes narrowed and his lips spread into a wide grin in what might be mistaken to be good humor. “Good. Good. I can learn from you, Thandi Gaines.”

Hamza called a yeoman over with strong tea. Goran added vodka to his. Perhaps with less of that he might have won the game.

“I believe there is the small matter of our wager, Director Hamza,” Li said.

“You bet on me?” Thandi asked the old fool.

“Fortuitously, as it turns out.”

Hamza felt the heat of her regard. “Wait – what did you bet him?” She struck the word him as if it were a stinky goat she’d found devouring her flower bed.

Hamza saw an opportunity and seized it. “Dongsheng has been wagering throughout our trip. I have already won the rights to three thousand parcels of Mars set aside for Jade Crane Partners. He was about to cede point-seven percent of the Tianlong.”

“The ship?” Genuine hurt moistened her eyes. Good. Good. Anything that split these two was to his benefit.

Skipper Dong looked up from his tea. “You won. Tianlong remains ours.”

“For now,” Hamza corrected. “Osman Consortium has certain options, as per the buy-out agreement.”

“The agreement you drafted,” Thandi said through gritted teeth. The one you jammed down my fiancé’s throat.

***

The memory glowed, looping back on itself, a captive moment performing its trick of joy over and over, all within shimmering borders that hovered in front of the bulkhead. Dongsheng and his new bride. Young! The faces were sharp, made up by a starving artist who wasted no valuable pigments on wrinkles or blemishes. The newlywed Jiaoxian was a beaming Earth mother, her few extra pounds offering a bounty of ardor to her beloved Dongsheng. The groom’s eyes, meanwhile, were the eyes of a wolf, shifting from target to target, assessing each for its food value.

He looked to a small mirror on the wall. His eyes were still sharp but less hungry. Something had tamed the wolf, remaking him into a stuffed toy cub awaiting a child’s hug.

Thandi was angry. Dongsheng had asked she not show such emotion in front of Hamza. He had invited her to his modest cabin, hoping to make her understand.

“That pig never agrees to anything unless it’s to his advantage. You cannot make bets with that man!”

“He is an idiot. He knows nothing about Crusades. Did you see his face when you –”

“He’s not an idiot. He wrote the agreement!” She was struggling to keep control.

The agreement. The agreement that caught Yuxuan off-guard. His son was too much the dreamer. He had envisioned getting ahead of the three dozen corporations vying to control Mars. To do that, he commissioned not just a single colony vessel like the others had but a fleet of six great starships. The investment would have paid off handsomely in less than three years, but it had left Jade Crane ill-liquid, prone to an opportunistic takeover. Hamza’s Osman Consortium pounced.

The miscalculation led to a lopsided and forced deal. Hamza’s consortium leveraged an option on the Tianlong, should it fail to meet all goals of its current mission, as well as eighty-percent control of the vessels still under construction. Yuxuan fought but was only able to retain full autonomy and ownership of Tianlong and Jade Crane’s R&D branch. It was a… strategic move.

Maybe if he had been stronger. How ironic that the very pills slowing his certain spiral into oblivion came to him at the beneficence of Osman Consortium. Or perhaps irony was not the right word.

“You could have lost everything. You can’t play God,” Thandi scolded.

“Someone has to,” he chirped.

In response, she sprayed him with a disgusted and disgusting raspberry.

Thandiwe truly was the image of Jiaoxian, may she rest peacefully. Thandi would have made a formidable match for Yuxuan, raising him from his duty to a fuller life of both passion and contentment.

His son, Yuxuan.

His oldest, Guo, hung in Shendong’s mind like a silken tapestry, frayed and faded with the years but still lovely in his intricate nature. The dead have that trick. Jiaoxian. Yuxuan. They beckoned him to come to their land of forever springtime. Soon enough, my beautiful ones. Guo was always the perfect heir, tall, strong, brilliant. He had died in a nameless war fought by Jade Crane and Osman, then headed by Yusuf Osman, father of the consortium’s present director. Like two wolves, he and the dark-eyed Yusuf circled the opposition, an alliance of tottering nations, seeking out and exploiting their weaknesses. In those days, Dongsheng saw wisdom in expanding empires. He and Yusuf won, seizing land, resources, and enormous wealth. General Guo led the battles, falling in the final campaign. His son Guo was gone.

Later, Dongsheng’s health declined. The “blood demon,” his doctors called it. It was everywhere. Everyone knew this hungry demon was linked to Haverhill, the “restorative” wonder drug, but no government was willing to challenge this fountain of youth. The disease was treatable to an extent, and, unlike most people, Dongsheng could afford the pills. He got them in thirty-day quantities from their manufacturer, Qevlex, which was of course owned by Osman Consortium.

At first, Dongsheng insisted on continuing in his position. It was Yuxuan in a rare show of strength who had convinced him to step aside. “It is the duty of the old to get out of the way of the young.” Blunt words, but he had to admit the boy’s resolute tone was a welcome change. He knew exactly when his son’s body had grown a backbone. It had happened when Yuxuan started dating Thandi Gaines, the brash girl from the former United American Empire. She was not like most of that region of book-hating gun-fetishists. Thandi was Yuxuan’s light, his fire.

Dongsheng ascended to “chief consultant” (spirit guide), and Yuxuan assumed the mantle of Jade Crane’s CEO. Yuxuan embraced the great task. The Sun turned off the lights of Xi’an as yawning board members tried to keep up with Yuxuan’s driving determination. Was this the start of a day or the end of the previous one? No one could be certain.

Yuxuan wasted no hours, and soon began to neglect Thandi in favor of the needs of Jade Crane. He believed in his responsibility to the exclusion of all else.

And then the great task was taken from him by the former ally. One wolf fed upon the other, seeking out a momentary weakness and attacking, forcing a takeover. Yuxuan successfully protected the invaluable R&D unit as well as the Tianlong, but all else came under the control of Maliq Hamza and his consortium.

Thandi stood by him, but Yuxuan viewed himself as a failure and could not live with the shame.

Upon Yuxuan’s suicide, all power transferred to Dongsheng’s youngest son, Yichen. He was a good young man, newly married, loyal, and smart. He was not, however, possessed of the temperament to oversee the forced downsizing of the family business.

Standing aboard the Tianlong approaching Mars, Skipper Dong offered a silent wish that Yichen follow his instructions without fail. Everything depended upon his doing this. Skipper Dong could almost hear his wife soothing voice counseling, Trust. Yes, Yichen was a man to be trusted.

Thandi snapped Skipper Dong back to reality. “And what did you win? After all that, what was so vital that you risked a share in our ship and all she holds?”

Reaching into his pocket, he pulled out a small container and held it up to the light. “A two-month supply of worthless pills.” He smiled warmly at her and tossed the container in the trash chute.

***

“Mind if I join you?” Hamza’s smile was practiced, precise, soulless. Two of his goons sat nearby nervously watching like trained mastiffs.

It’s not as though she had a choice. She liked to eat in the main dining area with the rest of the crew rather than in the officers’ wardroom. She was late today; most of first watch had eaten. He sat his tray carrying spicey chicken shawarma directly across the table from her half-eaten burger, conspicuously arranging his two bottles of Coca Cola.

“You’re not drinking tea?”

“I thought I’d try one of your old-fashioned American favorites today.”

She’d been trying to cut back, but the sugar was calling to her. “I might indulge as well.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry. The galley chief tells me these are the last.” Hamza opened one container and poured it out into a large mug. He drank in front of her, then opened the second one, using it to top off the mug. Sip. Refill.

“This is so sweet,” he said, making an exaggerated face. “It’s no wonder your people have such a weight problem. Oh, would you like some?” He proffered the half empty bottle.

Thandi felt her anger rising. Each week, the galley chief renewed his supplies from the ship’s synthetics department. Coca-Cola didn’t just run out. Hamza must have bought up all of the bottles for the week. That meant it would be three days before she could get one. She offered a clipped “thank you” and took the damned bottle.

A com drone flew in between them. Forsyth’s head popped into being, spun around comically, then fixed its attention on Thandi.

“We have an issue, Chief,” the head said.

Forsyth was not an idiot; she knew Hamza was with Thandi. “It’s all right. You may speak freely.”

“We have a weaver issue on the northern hemisphere.” The bottom of the ship. While the southern hemisphere was largely made up of cargo holds containing all the essentials for their eventual landfall, it was Tianlong’s northern hemisphere – the naughty top beetle or top dragon or whatever – that contained command-and-control and all living quarters. “One of the weavers has gone FUBAR.” It was another one of Forsyth’s dirty old expressions. “It’s cut a hole in the hull’s protective sheath.” Thandi’s cuff warmed and lit up with a series of numbers and letters, showing her which section was now exposed to space.

A shadow crept over her, a shadow with hot garlic clove breath. Hamza had somehow slipped around the table and was now standing over her shoulder, closely examining the coordinates.

“I believe that is the skipper’s cabin, is it not?” he asked, not needing an answer.

***

Forsyth dutifully helped Thandi into her hard suit, checking each seal and joint as well as the charge on all critical systems. The suit’s configuration was awkward and would be more so in zero gravity, but it was the best protection she could have.

“Chief, that cannot be a coincidence. Hell, no weaver has ever done anything like this.” Forsyth’s concern was heartwarming, and she agreed someone had gotten to the weaver.

The loss of one section of the tatami posed no great danger. The fact that it was Dongsheng’s section chilled her. Hamza must have surmised that Nao was housed in that section of the ship, accessible only through the skipper’s quarters… or through the hull.

Hamza was no genius, but he must know that Nao not only optimized all ship functions but also contained all of Jade Crane’s R&D secrets, including some she’d only heard about in whispers. Hell, he could have gone to Mars on one of the transports surrounded by his own people. He had chosen to travel aboard the Tianlong, no doubt hoping to steal everything Dongsheng had worked for over the years.

How far was Hamza willing to go to get in there?

The EVA Prep chamber door slid open. Goran entered. “I’ve been briefed on the situation. A bad machine. You’ll need help out there.”

There were hundreds of people on board qualified to handle this work. Thandi needed to go because she needed to try and confirm sabotage. Now, the most likely saboteur was volunteering to join her.

“Hamza sent you.” It was not a question.

“Yes.”

Keep your friends close and your enemies close enough to push them out into space, she told herself. Of course, he might be thinking the same thing. It was a thorny situation. She had every reason to believe Goran had caused this problem. He may even be preparing to stage some sort of accident for her once they were on the hull.

It would not be difficult for one person to press a cutting torch against the other and simulate a catastrophic suit failure. The body would float away, somewhere near the orbit of Mars, much too small for optical sensors to find, not to mention being out of reach of shuttles. Neither Tianlong nor the transports could stop to retrieve them. So, lost forever.

The next few minutes were going to be interesting.

Forsyth added to the fun. “Chief, we’re now within Mars’ gravity well, gaining momentum on the…” Forsyth looked at Goran, then looked Thandi in the eye. She nodded for Forsyth to finish the thought. “…vector reassignment.”

Goran had his helmet on. He keyed his external speaker. “We’re not going to Mars?”

“’fraid not,” Thandi told him. She motioned for Forsyth to leave the chamber and opened the outer hatch.

***

“They may be out there for an hour or more,” Li told Hamza. “I suggest we monitor their progress from my quarters.”

The invitation struck him dumb. He followed the old fool to the lowest deck of Tianlong. Li unceremoniously raised his cuff to the sentinel outside his cabin door. The door slid open and the two men stepped inside. Hamza told his guard, a burly man with a perpetual childlike grin, to remain in the passageway outside.

The so-called skipper’s quarters were far less ornate than Hamza had imagined. There was a holo-pic floating near the far bulkhead, some plants, comfortable furniture in the modern Beijing style, and a few keepsakes. On the old man’s desk, another holo-pic hovered, this one showing his three sons.

“My condolences on your loss. I can only hope nothing happens to your youngest boy.”

“He is a smart young man. And he has resources to resist impolite visitors.”

So, the old man was still capable of sparring. Good. Good.

Li called up a large monitor, divided among several views outside. One was from a camera on the hull, which showed indistinct movement against the spectacular pink aurora of the deployed sails. Two more views popped up, from the helmets of Goran and Gaines.

***

“You could have sent one of your team,” Thandi said over the comms.

I can do this,” Goran answered coolly, his breath beating against his helmet mic. He was a fine specimen, but walking along the hull took a great deal of concentration and effort, and his lack of practice showed in his labored voice. His inexperience in space might work to my advantage.

“We’re coming to the exposed area,” she said.

“The cuts are precise. The weaver followed a plan. It even stopped and shut down after it removed the tatami.”

He said it matter-of-factly, like a doctor examining an incision. More to the point, he said it as if it were all fresh information. Did he not expect this?

Thandi held out her wrist and struck the comms button, then motioned for him to do the same. They could now talk to each other without anyone monitoring them.

“Good. I’ve been meaning to ask, is Goran your first or last –”

“My full name is Grigoran Vasily Kuznetsov.”

“Okay. Goran then.” She took a breath and got down to it. “I need you to be honest here, Goran. Are you and your stupid boss trying to kill me?”

“No. I – I –” He was genuinely struggling. “I like you.”

Was he blushing? It was impossible to tell through two faceplates. Wait. Am I blushing? “Good. I… like you too, I guess. But, Hamza or one of your team commandeered the weaver and sent it to do this.”

“I agree someone did this thing. But if it were Hamza, he would have told me. My comrades haven’t the brains between them to do this. Even if they did, why would they?”

“To see whether there is another way into the skipper’s quarters.”

***

“They’ve cut us off!” Hamza felt sweat trickle down from his armpits. The helmet feed cameras were gone. They had only the long-distance view from the hull cam. Even with the image maximized, the shifting lights from the hard suits made it difficult to make sense of what was happening on the hull. “What are they doing?”

Li was frustratingly composed. “Or do you mean to ask, ‘Who is doing what to whom?’ She is fire and likely to leave your man burnt.”

“Things could go the other way. Goran is formidable and well trained.”

“We’ll see. We’ll see.” Damn his Chinese reserve!

“What kind of game are you playing now? They could both die out there, old fool. You were the one who called an exchange of queens wasteful.” Goran had a team of four operatives on Tianlong. The rest were on the personnel transport ships, now trailing days behind them. Suddenly, Hamza felt his position far less solid than before.

***

“There. Is that an access panel?” Goran asked, indicating a defined rectangular seam.

“No. I don’t recognize it. But, look.” She pointed out several more along the perimeter of the region the weaver had cleared. “There can’t be that many access panels.”

They made their way to the haywire weaver. Each took out their tools and went to work diagnosing the bot’s systems.

“Nothing wrong. It’s operating at optimal efficiency.”

“Someone programmed it.”

“Not you?”

“No. You?”

“No.”

His eyes, what she could see of them, were filled with concern, or perhaps concern for her. She got no vibes from Goran indicating he was trying to harm her.

“Then who…”

The weaver stirred. Its main readouts flashed a blinding red, then cleared and printed out a simple message in Russian, Farsi, Chinese, and finally English.

“Get inside. NOW!”

***

Li drew himself up to his full height, still a hand’s width shorter than Hamza. “Wars should be fought by kings. Young men should not die for the ambitions of crusty old fools.”

“What are you playing at, old fool?” Hamza looked back to the entry door. Had Li locked it? It was doubtful Hamza’s cuff would open it, but perhaps he could work the controls from the inside and –

The door opened on its own, revealing Hamza’s guard, whose face had overwritten his innocent smile with an expression of concern. Meanwhile, another door had opened on the far side of Li’s quarters. Hamza raised a hand, motioning for the burly man to stay where he was. This is not for you.

“I give you a choice, Maliq Hamza.” Li stood by the inner door, which now revealed a large chamber alive with a lusciously inviting glow. “You can leave as you entered my quarters, no richer or poorer, or you may come and meet Nao.”

Hamza drew closer. The central core rose up before them, the energies dancing in flux, casting warmth and light and igniting Hamza’s avarice into a blazing fury. Nao. All the secrets of Jade Crane’s R&D branch. The cup from which a man might sip the sweet Vimto of immortality.

Hamza stepped towards the fiery pillar, ignoring the door in the outer room as it closed.

***

Thandi struggled to shift the weaver off the exposed portion of the hull. “We need it. It can tell us who programmed it to do this.”

“Don’t be an idiot! He said get inside, and that is what we are going to do!” Goran grabbed her arm, hauling her mag-loc boots away from the hull’s surface. He had to be careful. If they both fell off the ship’s hull, their EVA rocket packs could never match the ever-increasing acceleration of Tianlong’s miles-wide faerie wings. As best he could, he raced both of them back to the access hatch. That meant crossing a large swath of the exposed hull.

From inside her hard suit, Thandi felt his feet make contact one after the other with the hull. It was like being carried by a mechanical gorilla. The rhythm transmitted up through both sets of suit armor and the solid matter that was her body. Th-pock. Th-pock. Th-pock. RRRRRR AAAAAAA Th-pock. HHH KKKHHHHAAAAA RRRRRR. It was a new sound. A much much bigger sound. A grating, ugly sound.

Though she was bobbing about like a fool on Goran’s back, Thandi caught a glimpse of one of the large rectangles on the hull. It was rising outwards.

“Shit!” she cried, even as he shouted, “Der’mo!”

***

“What’s happening?” Hamza’s face went from bliss to terror in an instant.

“A challenge in structural design,” Dongsheng said dryly. “That’s what my engineers called it. They said the key was to allow one section to detach without impairing the unibody strength of the whole.” Dongsheng felt no fear; indeed, he felt a great calm overtaking him. So many difficult choices now culminated in this moment of success. He wanted a drink. “You searched for the great secrets Jade Crane has acquired, and they are here.” He did not mention that he had transferred most of the secrets to the operating systems and memory stores aboard Tianlong, now safely winging its way into the deep night.

Dongsheng took a ragged breath and continued, “My son, Yuxuan, gave himself fully to his work. He provided the framework for Nao, and then he mapped his own neural patterns, drawn from his emotional depths. Nao is an echo of the mischievous boy I once pulled from my koi pond. In a manner of speaking, Nao is Yuxuan.”

“Your son is alive.” Hamza said in astonishment.

“Yes.” Dongsheng’s eyes moistened. It was the one secret he had kept from Thandi. She must never know. It was too cruel. Here was Yuxuan’s face and voice. It was Yuxuan in so many ways, but a cool, calculating simulacrum of his son, missing that spark that touched the rest of humanity. Is this death kinder than any other? Dongsheng wanted to ask but could not.

Nao had been a major passion of Yuxuan’s. His passion should have been Thandi. “Yuxuan wanted to build a fleet of ships to colonize not only the outer moons of our solar system but also to choose one such body and build it into an ark for mankind. A moveable nest.

“We’re not going to Mars?”

“No, we – that is, my people aboard the Tianlong – are speeding to Ceres,” and after a delicious pause, Dongsheng added, “which they will then steal, leaving Earth and her petty kings far behind.”

With the ship’s enormous wings, they would reach it within a matter of months. The ship itself would then undergo a metamorphosis, becoming the center of construction of a new world on that inhospitable asteroid. At 600 miles across, Ceres contained enough water, minerals, and other raw material to support a human civilization indefinitely.

A new voice joined the conversation. “At first, I thought I should go with them. I thought they needed me. This was an error on my part.” The voice was Yuxuan’s. The central core fluxed in shades of blue and magenta, coalescing into some semblance of his son’s proud face.

Hamza was pale. “You are Yuxuan?”

“I am.”

“You are alive!” Hamza rasped. “It’s true. I doubted my own agents’ reports, but they were right. They said this project was a gateway to eternity.”

“It is. And I am so very sorry.”

Hamza’s eyes squirmed with the possibilities. “So, someone can be scanned and stored within this matrix. Such a man could later fabricate a new body and transfer himself back–”

Yuxuan/Nao cut him off. “There is no purpose in such action.”

The man who emerged from such a journey would not be the man who began it. Not a man at all.

Hamza’s jaw dropped a thousand miles even as Yuxuan/Nao continued. “I have had time to reflect and review all of Earth’s long history. It is clear that men like you, Maliq Hamza, would spend millennia in the hateful practice of amassing power and enormous wealth, sucking it from innocent billions, killing many in the process. It has always been this way. This gift of immortality would turn petty thieves into wrathful, ravenous gods.”

“No, I would use that time to reclaim the Earth. I would restore it to the paradise it once was!” He was pleading like a child watching his mother walk away, perhaps forever.

“That won’t happen,” Dongsheng said. “That’s not who you are. Not me either. Not anyone.”

“It is a moot point now,” Yuxuan/Nao explained. “I have expelled all of our propellent to avoid collision with Mars. We are now in an indeterminant orbit around the Sun. We no longer possess the capability to reach planetfall.”

Hamza turned to Dongsheng in anger. “You’ve killed us!”

Dongsheng chuffed. “I’m tired of me. I’m more tired of you. The gods should have stopped us both long ago, but they are so old they have turned to stone.” The two men regarded each other for a moment, before Dongsheng continued in a less morose tone. “For now, we have food and comfort, Maotai Baijiu! There will be time enough to debate why kings must get out of the way and let the young chart a new course.”

“Damn you,” Hamza hissed lamely.

“My MLF is my power reserve,” Yuxuan/Nao said. “It should last for several months, ending peacefully but with finality for all of us. Meanwhile, I can share some of what I’ve learned. I think you will find our discussions interesting.”

Hamza sucked a bitter breath through clenched teeth. His face was drawn, almost lifeless. In a tone blending curiosity and resignation, he said, “Yes. Tell me.”

Dongsheng left his son and his enemy to talk about the wonders of the universe while he went off to see about dinner. He did not mention that he had thrown out the pills he’d won on Crusades and only had enough left for a week or so. They were his Most Limiting Factor. Dumplings. Yes, dumplings. He had Jiaoxian’s recipe on a card somewhere in his desk.

As he rummaged, Dongsheng thought of his beautiful bride and of Thandi, and he smiled. He had no regrets.

***

Tianlong sped along the gravitational lines of Mars, borrowing power from the God of War and plunging forward into the night. Her lovely pink wings, now spread thirty miles in each direction, arrayed like those of a dragonfly. The vessel and all she contained were now wholly dependent on human ingenuity rather than Nao's skills. Using the extra push from Mars, Tianlong’s children would continue to the Asteroid Belt and their new home, Ceres.

This planetoid, of course, was not to be their ultimate destination. Once they were settled on Ceres, they would test the designs in the ship’s computers, transferred there by Skipper Dong and Nao; the designs for the new interstellar drive. Given time for development, the new drive could put tens of thousands of worlds within reach. It would take human muscle and hard work, but once built, the drive would cut their wanderings from millennia to just a few generations.

***

The obelisk was just as he would have wished. Not a grave marker, though it could be considered as such, it was a monument to the future of man. The artist had etched a few inspiring words on each of the four faces, a shout from the emotional deeps to the heart of the void.

The obelisk stood in the center of First Town, founded in the colony’s first artificial cavern, willed into being by humans now living billions of miles from the nest. Ceres, a welcoming mother, had surrendered her longtime place in the solar system decades earlier with no complaints.

The children of Shuang Tianlong – for that is what they called themselves: Children of the Double Sky Dragon – had moved quickly, constructing a vast series of underground cities. Within years, they had also built and perfected the new interstellar drive. It generated a field to encompass all of Ceres’s mass and send it moving progressively faster out among the stars.

The three of them stood alone at the base of the obelisk. The Founder’s Day Crowd had done its celebrating and headed off to find other diversions. Goran touched her shoulder in the familiar manner. “He had a vision. That is rare.”

“It got us this far,” she said. “Now, it’s up to us.”

Looking at the monument, Goran’s grandson Ilya said to the Premiere of Ceres, “That thing looks like a wiener.”

“It’s an obelisk, a rock within the rock that is our home,” Premiere Thandiwe Gaines replied with saintly patience. “Just as there are dreams within dreams. It’s up to us… up to you, young man, to make sure you dream the right dreams. Give the angels something to sing about!”

###

- Details

Okay, so I did my homework and read up on Alexander the Great and wrote a book of my own. Fine. Alexander and the Butcher is a great read. Hope you'll check it out.

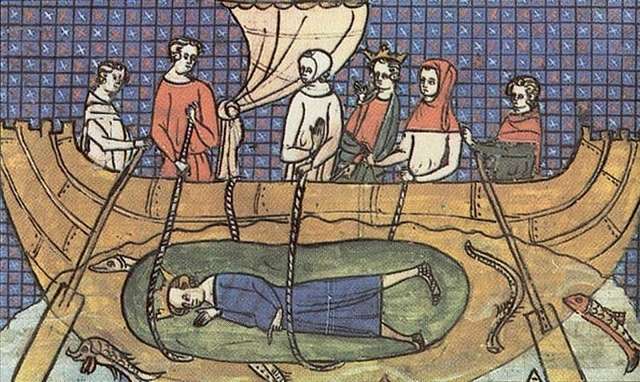

But... if Netflix comes calling, I may have to squeeze in one more chapter to accomodate Alexander's run-ins with... sea monsters!

https://greekreporter.com/2024/06/11/alexander-the-great-sea-monsters/

So... sea monsters. Hmmm. For now, I hope you'll settle for sex, magic, epic battles, amazing horses, and time travel.

Check out Alexander and the Butcher on Amazon now:

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Butcher-Chris-Riker/dp/B0D6PT9KX6/

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Butcher-Chris-Riker-ebook/dp/B0D7PKZHJN/

- Details

Don't mess with an ancient Macedonian if you want to hold onto your empire. No one doubts Alexander's magnificent track record on the battlefield -- undefeated. Al may have been Great, but he's still something of a mystery man. Now, archeologists are unlocking a few of his secrets...

I invite you to join me in imagining what it must have been like to ride and fight side-by-side with Alexander the Great. Hollywood actor Matt Wilder wonders what it would be like... and, unfortunately for him, he finds out. Alexander and the Butcher is available now!

Order your copy now from Amazon!

https://www.amazon.com/Alexander-Butcher-Chris-Riker/dp/B0D6PT9KX6/

- Details

You gotta fight like it's 331 BC!

(FREE EXCERPT)

Chapter One

The Diviner

A young Alexander galloped out of the California hills, his flaxen hair and confident grin visible from a distance as he raced his horse to the tents overflown by his father’s pennants. Swinging one bare leg over the animal’s powerful back, he executed a perfect running dismount, his sandals skidding to a halt on an X carefully drawn in the sandy soil. Taking a scant moment to adjust his purple-and-white tunic at the shoulder and hem, the young warrior rushed to his friend and clasped the man’s forearm.

“Menander!” Alexander pulled the other into a manly embrace, slapping him roughly on the back as battle-forged brothers do. As he turned to kiss him on the cheek, he whispered, “Stop looking up my skirt.”

Menander grinned back at Alexander, never breaking character. The good soldier pointed to Alexander’s uncomfortable passenger, bound and strapped over the back of his horse. “You bring a fine gift for your father, King Philip.”

Facing away from the camera, the bearded captive awkwardly raised his head of dark ringlets and spit at Alexander.

“Such are Persian manors,” Alexander responded. “Not to worry, sir. I will repay your impudence from our finest kegs. I will sail you home to King Darius on rivers of wine… after your tongue sings us to a Macedonian victory.”

Both Alexander and Menander laughed while their new captive fumed.

“Cut!” the director cried.

“Funny as always, Matt,” Glenn Givens said.

Matt appreciated Glenn giving his all as Menander, though, in Matt’s opinion, he drew from a shallow well. Matt’s contacts told him Glenn had another audition set up a few days after they wrapped, this time for the lead in a Western, sure money. The kids at home couldn’t get enough TV shows about scruffy men punching or shooting each other. The odds of the studio greenlighting both pilots were infinitesimal. Matt didn’t begrudge Glenn his ambitions, but he felt Glenn was better suited to play second fiddle to his, Matt Wilder’s, Alexander the Great.

Three men ran over and helped the stuntman doubling for John Carradine as the captured Persian general. They released his bindings, then lowered him ass-first from the horse’s flanks. “Thanks, Gary. I think we got your best side,” Matt joked. The stunt actor smiled back amiably and walked through the set, which had taken over a section of Vasquez Rocks Park. He passed the actual John Carradine, who was sipping an iced tea through a straw while using a giant sun reflector as a mirror to preen the curls of his glossy black wig and pointed beard.

A wrangler hurried over and took charge of the towering horse playing Alexander’s storied steed, Bucephalus. Matt wished he could bring Janey and Becca to the set. They’d love these horses. He kept meaning to teach them to ride, but the timing never worked out. Maybe he could get a trailer big enough for Jan and the girls to stay in during shooting hours, instead of leaving them in Sun Valley in a rental house surrounded by loud neighbors and crabgrass. How many times Jan had begged for a “simple drive to the ocean and maybe an overnight at a cheap hotel,” he’d lost count. They were living in their fourth home in five years, thanks to the vagaries of showbiz. Now, he was working steadily, meaning he was up and out the door by four a.m. and never home before the girls were in bed. Matt was becoming a stranger to his family. That could change, if the show sold.

Through his giggles, Matt urged the wrangler, “Give our boy extra oats on me. He’s a champ! Good boy, Flapjack! Good boy!” He gave the majestic Hanoverian’s neck two quick slaps in appreciation, earning a pleasant snort and nod in return. Sweetie! Like the horses he used to ride on his Grampa Ed’s ranch. To the director, Matt said, “Jack, I hope the mic didn’t pick up my ad lib. Couldn’t resist. We’ll fix that in looping, right?”

“As usual, Matt. Loved the dismount,” the director said. He got paid whether the pilot sold or not. The director treated Matt well – not because Matt was a nice guy; that was too much to ask for in Hollywood – but because he brought his natural athleticism and a raw cockiness that sold these action roles. Matt had worked hard on his physique and sported a well-defined chest, a steel-worker’s arms, and a ballet dancer’s nimble legs, a Frankensteinian assembly not lost on casting directors of the female persuasion. He also liked to do his own stunts, which won over directors burdened by a limited budget.

Matt needed allies behind the camera. In his early thirties, he was past the point of doing bit parts and in that tricky window of time. He’d either land the lead in a hit before his fortieth birthday or he’d spend the rest of his career playing the villain-of-the-week, the odd man out in a romantic triangle, or the forgettable walk-on.

The director called out, “We’ll take the bath scene after lunch, so eat light, everyone.”

Matt slapped his belly. “Tight as an army cot!”

They happily fled the tent city set and drove the forty-five minutes back to the relative comfort of the studio. The commissary had a hot meal waiting. Matt sat at the table with his co-stars. The supporting cast had another table, while extras – sixty of them had to give the impression of vast phalanxes – mulled about, eating beef stew out of paper bowls.

The legendary Carradine ate his meal quietly. He was a consummate actor but by no means social. He had made it clear he was “here to act, not make friends.” It was hard to fault him. The man had starred in Stagecoach, The Grapes of Wrath, and The Ten Commandments for Chrissake. More recently, though, he’d collected paychecks for low-brow fare like Sex Kittens Go To College! He’d also popped up on Wagon Train, Gunsmoke, and every other oater on the tube. He and Matt even guest starred in the same episode of Rawhide. They both bit the dust in that one. The point was that Carradine was a known quantity, a draw. People who couldn’t tell Matt Wilder from canned Spam would recognize Carradine’s saturnine face.

Matt would beat out Spam… if the series sold.

The Nordic sun appeared inside the commissary in the very female form of Ylsa Larsen. She joined them at the table, carrying only a salad. A decade younger than Matt, she was every inch the leading lady, and he fully appreciated all seventy of her inches – even if he had to stand on a stool for their close-ups.

“Finally, a ten at our table,” Matt said, beaming his little boy charm at her. The thought If I only were single… prompted a blush.

“You’re the prettiest one at any table, Matt.” He loved the mischief in her infinite blue eyes. She chided, “With that pretty golden hair and smooth chest, I’m sure half the men on this set would love to date you.”

That drew a laugh from Glenn, which robbed the grin from Matt’s face. “I don’t think the Macedonians shaved their chests,” Glenn said, beaming out a smile that hit folks with a big child-like innocence.

“That was a note from the boys in the front office. They like the hairless look.”

“I bet they do,” Ylsa snickered. She was right, Matt knew. For queer men on the make, a Hollywood studio office was the motherload. Anything, anytime, any- where.

“I don’t think I’d have to go that far to get a date,” Matt said. It was Glenn’s turn to lose his humor.

Into the awkward pause that followed, Carradine spoke up unexpectedly. “James Whale. Now there was a man who knew how to throw parties. And in those days, most people who were that way kept quiet. Not Whale. English expats indulge in forbidden fruit, you know!” With this last remark, he bugged out his eyes like a spaniel hearing a can opener. Then, as quickly as he had begun, he stopped and went back to eating his food.

Ylsa placed her hand on Glenn’s. “Live and let live, I say.”

Matt casually looked over at the far side of the lunch tent. After a moment, he turned back and said, “You and I should run lines later, for our scene.”

“The kissing scene,” Ylsa said, playing along.

“I seem to recall there being some kissing involved.”

She narrowed her eyes in cat-like fashion. “I see the rumors about you are well-earned, Matt. I think we’ll have to ration your rehearsals, tiger.”

Matt turned up his smile and leaned even closer. “Your character could be a regular love interest for Alexander. Or maybe we could recast you as his girlfriend – the one he marries. Roxanne.”

“Roxana,” Glenn corrected. “She was wife number one, and she murdered wife two and probably number three as well.”

“The good old days,” Matt joked. “No divorce lawyers.”

Glenn ignored his attempt at levity. “You should know this stuff by now.” Glenn had studied under Elia Kazan at The Actors Studio. He preached immersion in acting as the only true way to make the characters come to life. Matt respected his dedication, but it got on his nerves at times. “Did you read those books I gave you?”

From somewhere inside him rose Matt’s sixth-grade self, fidgeting at being caught blowing off his homework. “I did. I read and read, but… the names swim in my head. I’ve read books and seen Burton’s movie twice, but there’s something about Alexander that escapes me.”

“You and the producers. They’re not big on details. Today, they had a teenage Alexander – played by a thirty-something you – heroically capturing one of King Darius’ generals and delivering him to his father. Alexander doesn’t even invade the Achaemenid Empire until after Philip’s assassination by Pausanias of Orestis in 336 B.C.”

The names! Memorizing Shakespeare was child’s play compared to dealing with the intricacies of actual ancient history. An actor was athlete, fashion model, historian, chameleon – basically whatever the production called for. Matt’s eyes had glazed over. “Yeah, you make my point for me. Look, this is a family-oriented action adventure. I get that. I can’t rewrite the producers’ rewrite of history. What I want to do is find out who I am.”

Mischief flashed in Ylsa’s baby blues. “You should consult Madam Love.” Matt mouthed Madam Love with eyebrows raised. Ylsa shook her head and added, “She has certain insights.”

“What, a clairvoyant? Seriously? It’s the 1960s for goodness’ sake!” Matt didn’t want to laugh at Ylsa, but the thought of some old crone in a head scarf and gold earring peering into a crystal ball struck him as preposterous.

Ylsa pressed on. “She calls herself a diviner, a finder of truth. She’s an eccentric, but she gets amazing results. She’ll help you focus. Clear out bits you should really get rid of. She taps into your inner core and pulls out reserves of energy you never knew you had.” Matt wasn’t sure he wanted anyone rummaging around inside his skull.

“She’ll do you right,” Glenn added. “I had a sitting with Madam Love once. I learned –” His face went funny. “—a lot about myself.” He snapped his finger and someone at the next table put a pen in his hand, which he used to scribble information onto a paper napkin. “Here,” he said, handing the napkin to Matt. “I’ll call and set it up.”

“You both recommend her? Fine, I’ll check her out this weekend.”

Madame Love. This should be interesting.

*

Both Glenn and Ylsa were in the bath scene. Matt debated whether to wear the flesh-colored swimsuit or let it all hang out. It was tempting.

Steam rose from the heavy bronze tub as Ylsa poured another jug of water over Alexander’s distressed flesh. “My lord plays too rough. Look what they’ve done to your gorgeous back!”

The golden-haired son of Zeus braced under the near scalding torrent. “Yes, hot! That’s good! Darius has an army of lions. I felt their claws. Fortunately, their leader is no lion. He’s a sheep.”

Ylsa reached for another piping hot jug, but Menander appeared and took it from her. He poured the hot water over Alexander’s head. “Sheep, lions, or wild hares, they badly outnumber us, sire,” he said.

“Oh!” Alexander laughed and shook water from his flaxen mane. “My father’s armies are more than a match for any Persian horde. Like cunning Odysseus, we will use our wits. Tomorrow, we scout a field to the northeast for the coming battle.”

“Which battle?” Menander asked with alarm. “Your father has mentioned nothing of a new offensive.”

“Oh, Alexander, you mustn’t. I would simply die if anything happened to you!” Ylsa’s character – unnamed in the script, probably a slave girl – threw her arms around him and wept.

“I’ll turn those tears into tears of joy! I shall lure in Darius’ men at a time and place of my choosing and give them a taste of the Macedonian phalanx.” The camera came in for a close-up of Alexander’s self-satisfied face. The sound mixer would add a stab of dramatic music in post-production. Matt paused a moment, then said, “That sounds dirty, ‘taste of the Macedonian phalanx.’” There it was again, that patented Matt Wilder giggle.

“Cut!” the director shouted, though the scene was clearly over already.

“Johnny! That line.” Matt didn’t look around but spoke loudly enough to fill the set with his intent.

The nervous young scriptwriter, Jonathan Goldwasser, appeared as if summoned by a spell, flipping through the script to the offending line. He was college-educated and a fine writer but had signed away his soul and now toiled at the whim of the producers. “Uh – how about ‘taste of our mighty spears’?”

More giggling. “Same thing. The problem is taste and … well, anything that sounds like a… you know.”

“A penis,” the director said, helpfully. The crew’s snickering filled the set.

“Nothing wrong with that,” Ylsa mused aloud, not missing a beat. “Since we’re all dressed for an orgy.” The idea of a beautiful woman speaking the way men wished women talked reduced the crew to a mass of sophomoric glee. Their laughter rang louder than it had for any of Matt’s jokes, something not lost on him.

The others didn’t understand. Sure, they thought he craved attention. If so, it was for a purpose. He was the center of gravity holding them all in his orbit. This series would either succeed or disappear along with countless other TV pilots, based on how executives and test audiences reacted to him, Matt Wilder. The future of everyone on this cast and crew, their mortgage payments, their kids’ braces, their trips to Disneyland, all rested squarely on his shoulders.

Confirming it with the director, Matt made the announcement, “That’s it for today, folks.” He drank in the big cheer. Finally. “I’ll see everyone here on Monday morning, five a.m.! Get some rest and come back in full fighting mode! Let’s take this job seriously, but let’s have fun!”

Mumbles of agreement filtered back through the soundstage. Not as much enthusiasm as he’d like. They’d learn.

*

The radio gushed about the first lady looking stunning in an “Oleg Cassini original mauve silk chiffon embroidered with hand-sewn crystal beads. The Kennedys welcomed the president of India to the White House --” Matt clicked it off. He drove his gleaming new Shelby Cobra into the driveway, narrowly dodging a pink tricycle. It was late. The ninety-minute commute turned into three hours on Fridays. L.A. was killing him.

The living room was barren and cold.

“I’m home.” The silence that followed seeped all the way in.

The kitchen’s saloon-style doors swung open, and Jan stepped out in her floral A-line dress. She looked as young and fresh as she had on their wedding day, but something was missing. He used to look forward to her big goofy smile; it had been the light of his life. Lately, though, it was if she’d stopped caring. At night, one question circled his brain, digging cruel grooves into the gray matter: had he also stopped?

“I fixed you a plate,” Jan said. “Salmon and asparagus.” His favorite. “It’s in the oven.”

“Thank you.” It was all perfunctory. The magic was definitely slipping away, replaced by domestic banalities. “You and the girls ate already?” Without me?

“It’s eight-thirty, Matt. In case you hadn’t noticed, we’re not doing well-enough to dine Republican. Yes, we’ve eaten.”

She didn’t ask about his day. He wanted to tell her, but her antennae were in; she wasn’t receiving. He looked around.

“The girls are getting ready for bed.” Jan’s voice was steady, controlled. That was never a good sign.

“I want to tell them the news. I spoke with our head wrangler, and he says Janey and Becca can come ride Flapjack. Well, they can sit on him, anyway. They can take lessons later. He’s the sweetest horse I’ve ever met. They’ll love him.”

“You love him. They want a pet of their own, not a loaner dog… and not a horse. You love horses. You spend more time with that wrangler than you do with your own family. Hell, we come in behind the damned horse! Don’t go filling their heads with ideas of horseback riding lessons. We don’t have that kind of money either. We could have, but, of course, there’s your two closets full of new clothes and your trips to the beauty salon…”

“She’s a professional hair stylist.”

“…and the fencing lessons.”

“Weapons training, spears and swords; I have to keep in practice with both.”

“And of course, there’s that giant toy parked in the driveway.” That was a low blow, even for Jan. Recent Jan. Early Jan would never harbor this kind of bitterness.

“I have to present a successful image,” he argued. “You know that.”

She crossed her arms. Uh-oh. “Your image. So, you drive a two-seater?”

"You can’t expect me to take the station wagon to work.” Never mind that it was more rust than car, or that it was loaded with the girls’ toys and smelled like fermenting carnival candy.

“No,” she said like the axeman making small talk with the condemned, “You’d look ridiculous with a starlet on your arm behind the wheel of a family car.”

“Jan…” He took a breath. “What if you and I slip out and catch the late show. Burton’s Alexander is still playing at the Bijou.”

Her foot tapped, driving an invisible nail into the floor. “Not again.”

“So, maybe we don’t actually watch the movie.” He brushed his fingers along her bare arm, the way she liked. The way she used to like.

And the storm clouds opened: “I’m sick of Richard Burton… and of Alexander. I’m sick of stubbing my toe on all your books. I’m sick of these hours. Matt, I’m done. I’m taking the girls to my folks’ place for a while.”

“In Rhode Island? What’s in Rhode Island? Those fat clams? Look, I know it’s been tough, but this pilot is going to sell – I can feel it. Things will change fast. You’ll see. I’ll be making real money. We’ll get a better place. You’ll come with me to parties and events.”

“That’s your dream, Matt. And I love that you have a dream. But it’s not mine.” Someone was trapped behind those eyes, a prisoner willing to take desperate chances to escape. “I need a home and dinner at six and bills that get paid and… I need… I don’t know what I need, but it’s not this.”

As if on cue, the girls thundered into the room dressed in towels and chased by the neighbor’s water-logged terrier. He hated dog-sitting, even if they were paying Jan ten dollars. The animal positioned itself dead center in the room and shook, spraying the entire contents of the tub from its fur onto the walls and furnishings.

“Rufus! You’re not supposed to get in the tub!” Flustered, Jan chased the dog out the back door and into the yard. He’d no doubt roll in the nearest compost heap, negating any effects of his bath with the girls.

Matt, meanwhile, was spinning Becca under one arm and Janey under the other, their swinging feet narrowly avoiding lamps and other breakables. The girls felt tiny in his thick arms – the sessions with his physical trainer were really paying off!

Jan returned, a bedraggled expression breaking through her former composure. “I just got them quieted down.”

“Don’t blame me. It was Rufus’ fault. Wasn’t it girls?” Matt said, setting them down and tickling them mercilessly until their squeals shook the walls. “Hey, Daddy has a surprise for his favorite girls. We’re all going to visit with Flapjack and –”

“Your horse?” cried Becca.

“I love Flapjack,” added Janey, who had never met Flapjack. “When, Daddy, when?”

“We’ll aim for next week, maybe –”

Now Jan glared at him. “Did you not hear what I just said?” He was actively trying not to remember it, but reality was both mean and insistent. “We won’t be here next week.” She shooed the girls back out of the room, threatening them with dire consequences if they weren’t in bed in ten seconds. The adorable pair of tornadoes roared up the stairs, leaving an uneasy calm in their wake.

“You don’t have to go to your mother’s, baby. There are only two more weeks left of shooting. We can –”

“I’ve booked the flight. We leave first thing in the morning.”

Matt’s heart sank to the bottom of the sea. “How long will you be gone?”

She sat down, her skirts puffing out a gust of exhaustion. “A few weeks. Maybe longer.”

*

Matt double-checked the address on the gravy-stained napkin. Glenn had a woman’s loopy-swoopy handwriting, but at least it was legible. He had the right place. Good. He’d already loaded his family into a taxi; he didn’t need any more headaches this morning.

The Saturday sun shone down on a 1920s California Bungalow that had seen better eras. Paint peeled away from buckling stucco walls under a tiled roof with pieces chipped or missing. Out front, a shirtless boy struggled to push a manual lawn mower outmatched by the dense thicket of weeds. He swerved to avoid a sad-looking ’49 Tucker that stood on cinder blocks in the middle of the yard. A woman of a certain age sat on the front porch, drinking from a tall glass of amber liquid, her eyes fixed on the sweaty teen.

Matt stepped out of his smart new ’63 Shelby Cobra, walking past the boy and up the steps. “You must be Madam Love.”

“No. She’s dead.” It was a conversation stopper, but the woman said it as casually as if she were announcing she’d run out of corn flakes. “I will do this.” Before Matt could ask anything else she stepped inside.

Matt stood staring at the door. He turned to the teenager and shrugged. The boy shrugged back. Undaunted, Matt stepped into the front room of the house.

Shabby drapes matched the worn fabrics on the outdated furniture. A sheer red kerchief lay draped over a single lamp, rouging the far side of the room. The walls held a number of photographs showing the woman he’d just seen standing next to a much older woman in flowing silk garb. Madam Love, he presumed. Possibly this woman’s mother. In one corner, a table stood waiting. A taper rose from an elegant silver candlestick, the only thing of any value in sight.

“Hello?” Matt tried, answered only by a cobweb or two.

It took a moment but the woman he’d seen earlier reappeared, the highball in her hand topped off. She had added some cheap baubles and rings to her schlocky ensemble, plus a crocheted shawl, red to match the room.

“And you are?”

“Sit.”

“Madam Sit.”

“Sit! Hinsetzen!” The German bark made Matt jump.

“Of course.” He took a stool by the table.

“Not there.” The woman spoke with clipped vowels and a d sound where the th should be. She pointed to a grungy couch, its ugly pattern dissolving in a collage of food stains.

As Matt awkwardly moved over, an arthritic orange tabby entered the room. It coughed up something wet on the rug, turned, and left the way it had come.

“Should I cross your palm with silver?” Matt asked, grinning.

“Twenty dollars American,” she said matter-of-factly.

He pulled out his wallet, noticing how her eyes counted the contents, and handed her a bill so crisp it snapped when she grabbed it.

“Do I get your –”

“My name is not important. You are Moze Vitkus.”

How does she know that? He hadn’t used his real name in years and even paid his publicist to keep it out of the trades. “I go by Matt Wilder now.”

“You are who you are. Denial is a fool’s delight.” She’s watched too many movies on The Late Late Show.

Matt began over. “I was told you could help me to –”

She didn’t let him finish. “I know why you come to me, even if you do not.” She took a long sip of her morning cocktail. “Your mission is to understand.”

“About Alexander the Great. The truth is I’ve done my homework. I’ve studied his life,” he said, “but I can’t seem to find the man himself – what drives him. He’s a military genius, of course, but the real Alexander is an enigma.”

She looked at him and through him. The woman – in his mind, he named her Frau Bonkers – pointed a poorly manicured nail at his eyes. “You are seeking to understand a man you think you know.”

“That’s right. I –”

She cut him off. Again. It was getting on his nerves. “I will raise your consciousness to a higher plane of learning. Hand me your keys.”

“Why do you need my car keys?” he asked.

The woman said, “I can’t have you getting up and driving off while you’re under the influence. Deaths are hard to explain to the police.”

“Someone died? Wait! I could die?” Matt asked with understandable concern.

“Scheißkopf! Nobody dies. Your keys.” It was not a request. He handed her the keys. “Besides, I need to go grocery shopping. I’m making Zigeunerschnitzel for supper.”

“Sounds delicious.” He had no idea what it was.

They got started on the business at hand.

She told him to clear his mind. “Open yourself to a life you have never seen, never known. Where you once believed you knew reality, you will see new possibilities. New truths. A new past and a new future.”

She’s laying it on a bit thick, he thought.

Frau Bonkers stepped over to a bookcase. From an ornate wooden box, she plucked a vial of yellow-white powder.

Now, we’re cookin!

The woman took the vial out of the room. He heard a tap turn on in the kitchen. The juxtaposition of mixing up a magic potion with the sound of water from the local reservoir broke the mood.

She returned and handed him a glass painted on the side with a scene of Yogi Bear carrying a stolen pic-a-nic basket while Mr. Ranger chased him. The glass held a dull yellow liquid.

“What is it?” he tried.

“Es ist ein Zeittrank,” the woman said curtly. Matt had no clue what she’d said, but she quickly added, “I will be watching.” This only added to his confusion. “Let the Zeittrank bring you clarity. Men need clarity. Few men find it.” Still, he hesitated. “Trinken!”

Matt gulped it down. The brew smelled like Yogi’s backside and felt slimy on his tongue. He hoped the aftertaste of ashes would fade. It didn’t. At the woman’s urging, he then laid back on the couch. He plopped his head into a cushion, raising motes of dried sweat and spent passion.

For a minute, nothing happened. He wanted to ask questions, but the woman waved her hand, indicating for him to be calm. She ordered him to shut his eyes and relax. It was a tall order.

Somewhere, an old clock ticked. Matt felt a tingling in his ear lobes, and enjoyed the lazy fireworks display playing on the inside of his eyelids. Otherwise, he felt nothing out of the ordinary. Then, as if someone had thrown a switch, his senses stopped. He no longer smelled the funky couch nor tasted the awful elixir.

For an instant, he lived in an insubstantial world which refused to connect to any of his senses.

“Has it started yet? When will this happen?” Matt asked, peeking out through one eye…

…and meeting blinding daylight.

“Now! Raise your sarissas, you lice-infested dogs!” An officer in a bronze breastplate cried over a tremendous rumbling. Matt was crouching in the dust, his hands clutching a long pole with a broad blade at one end. His clothes had been replaced by filthy rags that left his legs bare. Crude leather sandals, cracked and split in places, barely protected his feet. On either side of him, men hunkered down low. In unison, they angled up the eighteen-foot-long poles to expose their vicious blades. They braced the butt against the rocky dry ground. A slender line of equally ragged men, swords in hand, blocked Matt’s forward view. As soon as the officer cried out, these men ran behind those raising the poles.

This presented Matt with a full view he instantly wished he had never seen.

Men on horseback – perhaps fifty of them – were thundering down on their position. The horsemen wore colorful robes that whipped in the breeze. Underneath, they girded themselves in vests of ablative scales, turning them into giant warlike fish. They screamed battle cries loud enough to stop a man’s heart. The horde came heavily armed, raising spears, ready to deal out death. Some nocked arrows in powerful double-bent bows. Others swung oddly-shaped axes clearly intended to remove heads from bodies. The attackers, led by a bearded devil in a chariot, were bearing down on a meager foe. A farmer showed more mercy when slaughtering his chickens.

The chargers were seconds away from overrunning Matt and the others. He could already feel the bite of their blades. Death had come. The men around him showed no fear. If anything, their faces betrayed a dull acceptance that whatever happened next was beyond their control… or their caring.

Matt was less composed. “Mother!” he cried.

Chapter Two

The Man on the Horse on the Hill

The screams of the horses fired electrical terror through Matt’s body, as if he and the animals shared one nervous system. They were alike: pawns in someone’s game of war. Matt had served two uneventful years in the army after the Korean conflict. He’d never seen battle. Now, here he was in a war he’d only read about in Glenn’s books. Ancient history books. And here he was. Not reading. Not looking back. Right here.

Matt wanted to shut his eyes, but he could not will himself to do it. Instead, he gripped his bladed pole tighter like the men to either side of him.